Introduction

Chronic non-healing wounds present a substantial clinical and economic burden, affecting more than 10 million patients in the United States.1 These wounds often persist for months to years and are associated with impaired quality of life, pain, increased risk of infection and frequent healthcare utilization. Patients with multiple chronic conditions and risk factors—such as advanced age, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, renal failure, or immobility—are particularly vulnerable to delayed wound healing. Studies have shown standard of care treatment fails in 57.3% of venous leg ulcers (VLUs), 60% of pressure ulcers (PUs), and 62.1% of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs).2 Other studies have shown that among patients with chronic non-healing wounds refractory to standard care, 14.1% undergo amputation and 8.7% die of wound-related causes.3

These observations underscore the need for advanced treatments, such as cellular, acellular, and matrix-like products (CAMPs). By supplying a biologic covering for the wound, CAMPs provide scaffolding and protection so new tissue can generate while standard wound care continues. Clinical evidence, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), real- world evidence (RWE), and multicenter prospective studies, have demonstrated that CAMPs accelerate wound closure, reduce complication rates, and improve overall patient outcomes. By preventing medical complications, including amputations and hospitalizations, CAMPs can represent a cost-effective strategy for both improving patient quality of life and protecting the long term stability of our healthcare system.4

The objective of this retrospective case series is to review clinical outcomes in patients with high-risk factors and complex, non-healing wounds who had prolonged non-improvement (several months to years) and subsequently received CAMPs. By examining their clinical course, we highlight the significant role of CAMPs and the importance of timely access to advanced therapy.

Case 1: Older adult with sacral ulcer and multiple high-risk factors

Patient description

A 91-year-old woman presented with a 9-month history of a stage IV sacral ulcer (Figure 1). She was bedbound and required full assistance with activities of daily living, received enteral nutrition via gastrostomy tube, and had a Foley catheter for urinary incontinence. She lived with her daughter, her primary caregiver. Past medical history included bone and soft-tissue infections, hysterectomy, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, severe lumbar stenosis, osteomyelitis, and recurrent urinary tract infections with incontinence. She was receiving anticoagulation therapy and was therefore at elevated bleeding risk.

FIGURE 1 Case 1: Initial patient evaluation visit.

Case history

The sacral ulcer was evaluated as stage IV with a surface area of 97 cm2 and a volume of 310 cm3, with significant undermining from the 9 to 3 o'clock positions to a depth of 4.5 cm. Bone was exposed, and undermining was extensive. The wound bed contained approximately 40% devitalized tissue and 60% granulation tissue. Initial management included negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT; −125 mmHg), silver alginate, and a silicone-bordered dressing. NPWT treatment was discontinued due to patient’s high risk of bleeding. Clinical research guidance for wounds that fail to progress towards sufficient healing after 4 weeks of standard of care treatment should be evaluated for advanced wound care treatment.5 After the patient received over 4 weeks of standard of care treatment which included dressing with MediHoney, gauze and secured with silicone bordered dressing and air mattress, there was insufficient advancement towards healing and inadequate granulation to fill the wound base; the patient was therefore evaluated and qualified for advanced therapy.

Treatment plan and course

The case was reviewed by multi-disciplinary team and qualified for CAMP treatment due to: 1) lack of sufficient wound reduction (<50%) over the last 30 days; 2) appropriate standard of care treatment was provided to manage the wound; 3) no signs of necrosis, infection or osteomyelitis; 4) sufficient nutritional status; 5) offloading measures in place. The treatment plan included wound bed preparation with debridement to optimize for CAMP application. Preventive measures were instituted, including caregiver education on dressing changes, off-loading, and air-mattress settings. The wound was debrided five times over 9 weeks; the patient experienced a moderate level of bleeding and this was controlled with compression, and foam dressings were applied. The patient received 16 CAMP applications over the course of 15 months of treatment. The duration of the patients treatment was prolonged since she struggled with multiple hospitalizations for urinary tract infections,due to UTI and mismanagement of the wound. Despite these challenges the sacral ulcer progressed substantially towards healing, achieving a 97% reduction in surface area and a 99% reduction in volume by the time of case study completion (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 Case 1: Post-CAMP treatment

Discussion

This patient's numerous risk factors—non-ambulatory status, advanced age, recurrent UTIs with associated hospitalizations, and incontinence with intermittent Foley-related leakage compromising dressings—posed significant barriers to healing. Notwithstanding these challenges, the combination of rigorous wound bed preparation, preventive measures, and CAMP therapy was associated with marked reductions in wound size and improvements in undermining and tunneling, suggesting a meaningful role for CAMPs in similar high-risk profiles.

Case 2: Male patient with advanced sacral pressure ulcer during active pneumonia treatment

Patient description

A 74-year-old man presented with a stage III sacral pressure ulcer after being discharged from inpatient rehabilitation for stroke recovery. He was concurrently being treated for pneumonia and had recurrent UTIs. Past medical history included hypertension, stroke, and atrial fibrillation. He was bedbound, required full assistance with activities of daily living, and depended on a gastrostomy tube for nutrition. His wife—also elderly—was the sole caregiver; she had limited comfort with providing wound care dressing changes at home.

Case history

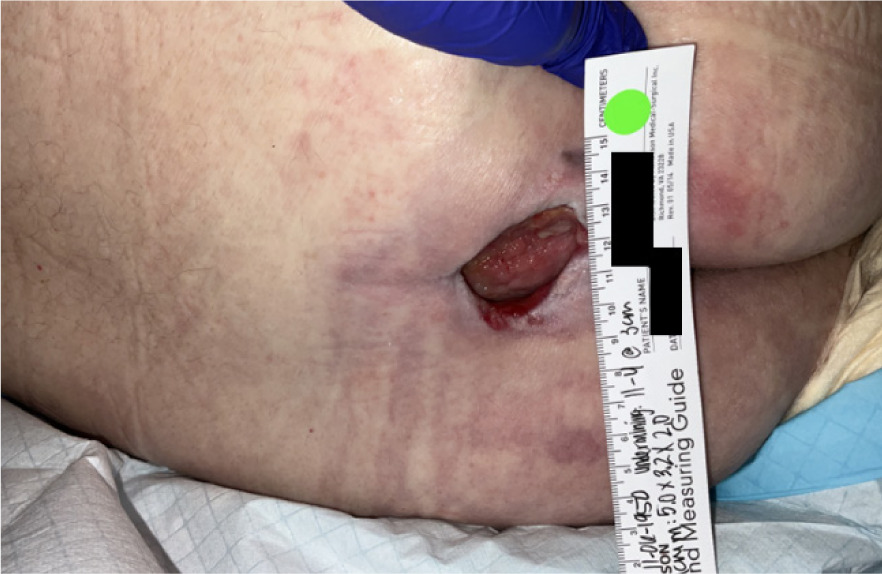

Over the 2 months following discharge, the sacral ulcer progressed from stage II to stage III. On evaluation, the wound surface area was 97.5 cm2 and volume was 32 cm3, with significant undermining from 11 to 4 o'clock at 3 cm, and tunneling at 7 o'clock to 2.5 cm (Figure 3). Initial management included NPWT at −125 mmHg and silver alginate packing with silicone-bordered dressings changed two to three times weekly or as needed. After receiving over 4 weeks of standard of care treatment (i.e. dressings and NPWT) without adequate edge advancement or granulation, the patient was deemed appropriate for advanced therapy.

FIGURE 3 Case 2: Initial patient evaluation visit

Treatment plan and course

The case was reviewed by multi-disciplinary team and qualified for CAMP treatment due to: 1) lack of sufficient wound reduction (<50%) over the last 30 days; 2) appropriate standard of care treatment was provided to manage the wound; 3) no signs of necrosis, infection or osteomyelitis; 4) sufficient nutritional status; 5) offloading measures in place. An advanced wound-care plan combining CAMPs with NPWT was implemented. Wound bed preparation included irrigation and fibracol packing to address undermining and tunneling, followed by NPWT for exudate control and to support perfusion. CAMP was applied to the sacrum, covered with a contact layer (Adaptic) and fibracol, and NPWT (−125 mmHg) was resumed. The patient received 10 weekly CAMP applications. The wound achieved a 70% reduction in surface area and a 93% reduction in volume (Figure 4). Hyperkeratosis and epibole were managed with debridement and cauterization. The patient later died from pneumonia unrelated to the wound.

FIGURE 4 Case 2: Post-CAMP treatment

Discussion

Despite the patient struggling with an acute lung infection, the combination therapy of CAMPs and NPWT was associated with substantial wound improvement. Since NPWT was being used on wound prior to beginning CAMP treatment, results can be attributed to the use of CAMP and NPWT supporting the uptake of the graft. Prior work suggests that pairing skin substitutes with NPWT may accelerate vascular ingrowth and graft uptake.6 Animal models indicate that during severe infections such as pneumonia, immune responses may prioritize life-threatening processes over dermal repair.7 Additional research is needed to elucidate immune prioritization in the context of concurrent infection and wound healing.

Case 3: Female patient with dementia in memory care treated for VLU with fat layer exposed

Patient description

An 84-year-old ambulatory woman residing in a memory care unit of a skilled nursing facility presented with a 3-month history of a non-pressure lower-left-extremity ulcer due to venous insufficiency. Past medical history included Alzheimer's disease, hypertension, chronic atrial fibrillation, kidney disease, myotonic dystrophy type 2, and prior bone/tissue infections.

Case history

At presentation, the ulcer involved exposed subcutaneous fat with a wound area of 112.5 cm2 and a volume of 22.4 cm3; the base was fibragranular, and no edema was noted (Figure 5). The patient reported severe pain. Standard of care treatment by the SNF wound-care team included conservative debridement and dressing changes, along with a 2-week course of antibiotics for a wound infection. There was not sufficient improvement of the wound towards healing indicating failure of standard of care treatment. Laboratory assessment showed HbA1c 8.1%. The ankle-brachial index (ABI) of the left foot was 0.9, consistent with mild peripheral arterial disease. The patient was referred for advanced wound care and to be considered for CAMP application.

FIGURE 5 Case 3: Initial patient evaluation visit

Treatment plan and course

The patient was reviewed by multi-disciplinary team and qualified for CAMP treatment due to: 1) lack of sufficient wound reduction (<50%) over the last 30 days; 2) appropriate standard of care treatment was provided to manage the wound; 3) no signs of necrosis, infection or osteomyelitis; 4) sufficient nutritional status; 5) ABI index > 0.6; 6) documented use of compression therapy. Prior to the first application, the wound showed no clinical signs of active infection. The VLU was cleansed to disrupt biofilm and debrided to a granular base. CAMP was applied and secured with a contact layer to permit drainage and with Steri-Strips. As exudate was not heavy, Adaptic and ABD pads were used as secondary dressings. The patient received seven CAMP applications over the course of 8 weeks with concurrent compression therapy. The wound achieved 100% reduction in both surface area and volume (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 Case 3: Initial patient evaluation visit

In addition to CAMP therapy, conservative care included daily secondary-dressing changes to manage exudate, appropriate cleansing, and debridement during CAMP applications to limit biofilm burden. The patient adhered to single-layer compression during the day and leg elevation at night. A practical challenge was occasional patient refusal of care related to advanced dementia, necessitating the daughter's presence during CAMP visits.

Discussion

In order for VLUs to heal they require for patients to be compliant with compression socks and elevation of leg which is the standard of care treatment. Studies have shown that VLUs treated with standard of care heal but with a longer period to closure of approximately 77 days.8 While the case study patient achieved healing with 25% less time, comparatively.

Patients with dementia are at elevated risk for chronic wounds due to their existing comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, venous insufficiency) and functional limitations (e.g., immobility, incontinence, malnutrition).9 Cognitive impairment associated with dementia can hinder comprehension and acceptance of care plans, as seen in this case, and may delay timely interventions.10 A key factor in this patient's healing was reliable access to CAMPs coupled with consistent wound management (daily dressing care, compression, and elevation). Current literature and standard care pathways seldom address the unique needs of patients with dementia and chronic wounds, who may be underrepresented in research.11 Further study is warranted to develop tailored wound-care guidelines for this population and to evaluate the impact of CAMPs on healing, pain, and quality of life.

Case 4: 75-year-old female presented with an 8-year history of a chronic, non-pressure ulcer on the lower right leg with multiple ulcerations

Patient description

The patient was ambulatory with assistive devices. Her past medical history included type 2 diabetes, lymphedema, neuropathy, congestive heart failure, arthritis, gout, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), venous insufficiency, prior MRSA infection, bone and soft tissue infections, and sickle cell disease (SCD). Her surgical history included bilateral knee replacements, right foot shaving, appendectomy, and cholecystectomy. She resided with her daughter, who was also her primary caregiver.

Case history

On presentation, the lower right extremity ulcer measured 330 cm2 in surface area and 99 cm3 in volume, with fat layer exposure (Figure 7). The wound was characterized by 45% epithelial tissue and 55% granulation tissue, with multiple ulcerations and mild edema.

Due to the combined effects of venous insufficiency and recurrent sickle cell crises, the wound had been refractory for years, with frequent exacerbations. Heavy exudate contributed to maceration and the development of new ulcerations. Prior to referral for advanced wound therapy, the patient received conservative care, including wound cleansing, dressing changes, and compression therapy. However, she was frequently non-compliant with compression. Severe pain related to SCD further impaired adherence and negatively impacted her quality of life.

FIGURE 7 Case 4: Initial patient evaluation

Treatment plan

Patient case was reviewed by multi-disciplinary team and qualified for CAMP treatment due to: 1) lack of sufficient wound reduction (<50%) over the last 30 days; 2) appropriate standard of care treatment was provided to manage the wound; 3) no signs of necrosis, infection or osteomyelitis; 4) sufficient nutritional status; 5) ABI index > 0.6; 6) documented use of compression therapy.

Given her history of failed therapies, the patient was evaluated and qualified for cellular, acellular, and matrix-like product (CAMP) therapy. The treatment plan included:

-

Wound bed preparation: 7 weeks of conservative care, including cleansing and debridement, were used to optimize the wound bed prior to CAMP initiation.

-

CAMP application: Once the wound was ready, the patient received five CAMP applications over a 14-week period.

-

Adjunctive therapy: Light compression therapy (one-layer compression due to PAD and SCD) and leg elevation were prescribed.

Challenges during treatment included continued non-compliance with compression therapy and frequent dressing changes due to heavy exudate. During the treatment period, the patient developed cellulitis, requiring antibiotics and temporary suspension of CAMP therapy. She was subsequently admitted to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) to ensure adherence to compression therapy and wound care. Despite these complications, the wound fully healed within 14 weeks of initiating CAMP therapy (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8 Case 4: Wound healing after treatment

Discussion

Sickle cell leg ulcers (SCLUs) are notoriously painful, slow to heal, and severely impact quality of life.12 Currently, there is no standardized treatment protocol for SCLUs, and studies report that they may heal up to 16 times slower than VLUs.13

This case highlights the importance of advanced wound technologies, such as CAMPs, in achieving closure of chronic, non-healing wounds in patients with multiple comorbidities. Even in a patient with limited compliance and significant systemic disease burden, CAMP therapy facilitated complete healing in 14 weeks.

Optimal treatment of SCLUs likely requires a holistic approach that combines CAMPs with compression therapy, adequate wound care, infection control, and nutritional support. Future research should aim to establish standardized protocols for the management of SCLUs.

Case 5: Elderly ambulatory male with chronic non-healing pressure injury on right lower extremity

Patient presentation

An 87-year-old ambulatory patient, requiring assistive devices, presented with a chronic non-healing pressure injury of the lower right extremity following discharge from a rehabilitation facility. The patient's past medical history was significant for cerebrovascular accident, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, recurrent stroke, chronic osteomyelitis, and a history of recurring wounds. The patient resided at home with family support from children.

Case history

The patient presented with a non-healing wound on the right lower extremity (Figure 9), attributed to pressure from a rehabilitation boot, with a duration of >3 months. On initial assessment, the wound measured 25.5 cm2 in surface area and 8.65 cm3 in volume. The wound bed demonstrated excessive hypergranulation tissue, accompanied by mild leg edema. Prior management by home health nursing services included alginate dressing changes; however, the wound failed to demonstrate progression toward healing.

FIGURE 9 Case 5: Initial patient evaluation

Treatment plan

Patient case was reviewed by multi-disciplinary team and qualified for CAMP treatment due to: 1) lack of sufficient wound reduction (<50%) over the last 30 days; 2) appropriate standard of care treatment was provided to manage the wound; 3) no signs of necrosis, infection or osteomyelitis; 4) sufficient nutritional status; 5) ABI index > 0.6; 6) documented use of compression therapy. Prior to initiation, wound bed preparation was required due to excessive hypergranulation. This was managed with weekly silver nitrate cauterization and dressing changes performed three times per week, using Xeroform, Adaptic, and dry sterile dressings.

The patient received 5 weeks of conservative wound optimization, including repeated cauterization to reduce hypergranulation. Education was provided to both the home health care team and primary caregivers regarding appropriate dressing techniques. Once the wound bed was adequately prepared, CAMP therapy was initiated. The patient underwent 10 weeks of CAMP application, ultimately achieving complete wound closure and recovery (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10 Case 5: Wound healing after treatment

Discussion

This case underscores the importance of timely escalation to advanced wound therapies in elderly patients with chronic non-healing wounds, particularly when complicated by multiple comorbidities. It highlights the need for a comprehensive and holistic approach, which not only includes advanced biologic therapies but also incorporates nutritional optimization, edema management, and caregiver education. By combining wound bed preparation with CAMP application, full healing was achieved in a medically complex patient who had previously failed standard care.

Conclusions

In this retrospective case series of five medically complex patients with chronic non-healing wounds, CAMP therapy— often in conjunction with meticulous wound-bed preparation and, when appropriate, NPWT—was associated with substantial improvement or complete closure. Ensuring timely access to advanced therapies improves outcomes in medically complex and high-risk populations.