Introduction

Non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC), primary basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), represent the most frequently diagnosed malignancies globally.1-3 The incidence of these tumors continues to rise globally, representing an escalating public health concern.3-5 BCC is the most common subtype, accounting for approximately 75% of NMSC cases,6,7 and typically exhibits slow growth with low metastatic potential. SCC is the second most common skin tumor. It can be more aggressive, with a higher propensity for local invasion, with a regional and distant spread.8,9 The metastatic rates for SCC range from 2-6 %.10 Despite their generally favorable prognosis when detected early, these skin cancers can lead to significant morbidity and disfigurement, particularly when affecting anatomically sensitive or cosmetically critical areas such as the head and neck.11-13

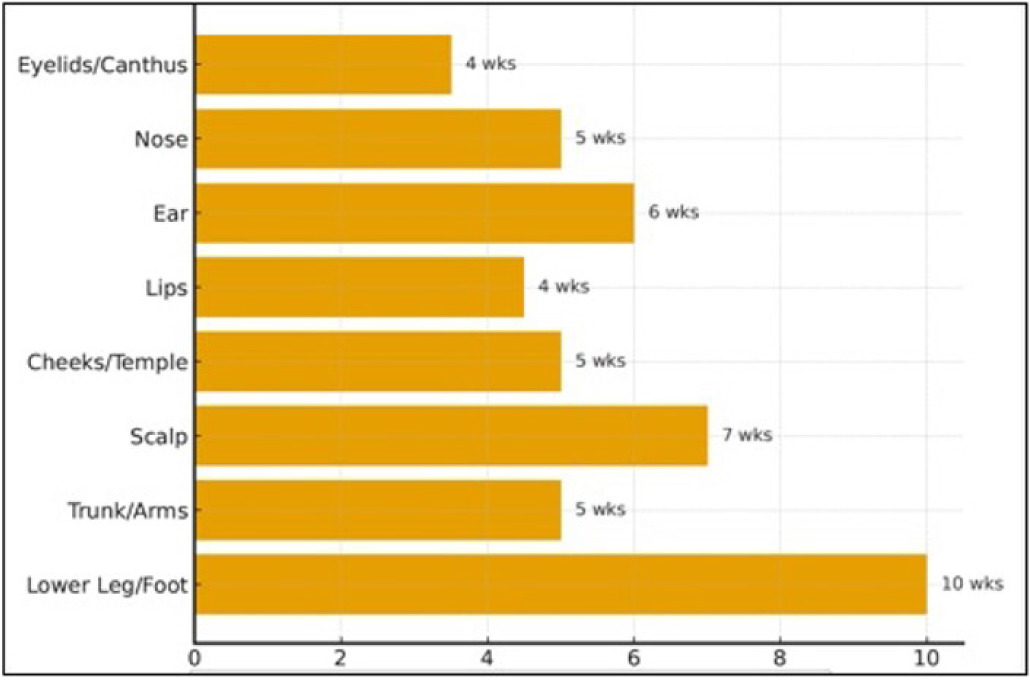

Effective management of NMSC, particularly high-risk or recurrent SCC, is crucial for achieving optimal oncologic control and preserving the function and aesthetics of the affected area. For decades, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been regarded as the gold standard for treating these challenging cases.14,15 Its meticulous, layer-by-layer excision with real-time microscopic margin control allows for maximal tumor eradication while conserving healthy tissue, thereby minimizing wound size and facilitating reconstruction.16,17 Despite the precision of MMS, post-surgical wound reconstruction can be challenging, particularly for larger and deeper NMSC defects.18,19 Traditional closure techniques, including primary closure, healing by secondary intention, split-thickness skin grafts, or local flaps, are not always feasible and may result in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome or delayed wound healing.15,20 It is challenging to reconstruct areas such as the scalp and distal lower extremities, which are frequently left to close by secondary intention; however, the wound closure may take up to 12 weeks (Figure 1).21-25

FIGURE 1 Secondary intention healing times following Mohs micrographic surgery. Estimated average healing durations by anatomic site are shown. Concave and highly vascularized areas (e.g., eyelids, medial canthus, perioral region) typically heal within 3–4 weeks, whereas convex or poorly vascularized sites (e.g., periosteum, cartilage, distal third of the lower extremities) may require 6–12 weeks or longer to heal. Healing time is influenced by wound size, depth, vascularity, and patient comorbidities.

Protracted healing times and the potential for infectious complications associated with healing by secondary intention led to the search for reconstructive alternatives. Cellular, acellular, and matrix-like products (CAMPs) have emerged as a promising addition to the management of complex post-MMS wounds. Among the CAMPs, products derived from placental membranes have gained significant attention due to their unique biological properties.26,27 Tri-layered amniotic membrane (Amnio Tri-Core, Stability Biologics, San Antonio, TX, USA) is composed of three layers of amniotic membrane. The product is classified as a human tissue product and has been cleared for clinical use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under the HCT/P 361 pathway.

This retrospective study aims to evaluate the clinical outcomes of 46 patients undergoing MMS for the removal of multiple NMSCs in regions such as the face, limbs, and neck, with subsequent wound reconstruction using a tri-layered amniotic membrane CAMP administered weekly.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a multicenter (10 locations across Florida, United States) retrospective study evaluating the clinical outcomes of patients who MMS for the removal of NMSC located in anatomically sensitive or cosmetically critical areas, including the face, limbs, and neck, with subsequent wound reconstruction using tri-layered amniotic membrane. Wound-level analyses were performed per wound rather than per patient. Because some patients contributed more than one wound (94 wounds from 46 patients), PAR and wound-volume calculations were conducted at the wound level.

Ethical considerations and patient consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was submitted to the WCG Institutional Review Board (IRB), which determined the research to be exempt from IRB oversight under the United States federal regulation 45 CFR 46.104(d)(4) for the secondary research use of identifiable private information (IRB Study #1390743).

Given the retrospective design of the study, which relied exclusively on the review of existing electronic medical records, the IRB granted a full waiver of the requirement to obtain informed consent from individual patients. Furthermore, a waiver of authorization for the use and disclosure of protected health information (PHI) was approved under 45 CFR 164.512, as the research involved no more than minimal risk to the subjects and could not practicably be conducted without the waiver.

To ensure patient confidentiality, all data were de-identified before analysis. The extracted information was compiled and stored in a secure, password-protected digital format, with stringent measures in place to maintain the privacy of all individuals and comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Selection criteria

Patients were eligible if they were ≥18 years of age, had been diagnosed with NMSC, such as SCC or BCC, and underwent MMS. There were no exclusion criteria for underlying conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, or sun exposure). Patients with incomplete medical records or allergies to vancomycin, gentamicin, or Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) as used to process the graft tissue were excluded.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic information, medical history, and lifestyle factors for the 46 patients included in the study. Values are presented as the number of patients (N) and percentage (%) or as Standard Deviation (SD), Median, and Range for continuous variables.

TABLE 1 Patient demographics and baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Total patients (N) | 46 |

| Age (years) Mean ± SD Median (range) |

79.4 ± 7.6 79 (60-101) |

| Sex (N, %) Male Female |

28 (60.9%) 18 (39.1%) |

| Allergies (N, %) Any reported allergy Penicillin Sulfonamide antibiotics Aspirin Latex Unknown |

17 (37.0%) 7 (15.2%) 5 (10.9%) 1 (2.2%) 2 (4.3%) 1 (2.2%) |

| Implant devices (N, %) Pacemaker/defibrillator Other implants (e.g., stent, joint replacement) |

1 (2.2%) 5 (10.9%) |

| History of chemotherapy (N, %) | 0 (0%) |

| Currently taking blood thinners*(N, %) Yes No Unknown |

11 (23.9%) 27 (58.7%) 8 (17.4%) |

| Smoking status (N, %) Never smoker Ex-smoker Current smoker Unkown |

22 (47.8%) 15 (32.6%) 1 (2.2%) 8 (17.4%) |

| Alcohol consumption (N, %) Non-drinker Social drinker Ex-drinker Unknown |

17 (37.0%) 22 (47.8%) 2 (4.3%) 5 (10.9%) |

| Regular exercise (N, %) Yes No Unknown |

21 (45.7%) 14 (30.4%) 11 (23.9%) |

| Selected comorbidities (N, %) Hypertension Diabetes mellitus Arthritis Osteoporosis High cholesterol/triglycerides History of prostate cancer History of malignant melanoma Hepatitis |

12 (26.1%) 6 (13.0%) 10 (21.7%) 2 (4.3%) 3 (6.5%) 2 (4.3%) 6 (13.0%) 1 (2.2%) |

*Includes antiplatelet agents (e.g., Aspirin, Clopidogrel) and anticoagulant agents (e.g., Eliquis, Warfarin, Xarelto).

Data collection

Data were collected retrospectively from patient records. The following variables were recorded:

-

Demographic information: age, sex, and comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, or past surgeries).

-

Wound characteristics: type of NMSC removed, location, and size.

-

Treatment details: use of antimicrobial agents before and after MMS, number of graft applications, and additional wound care interventions.

-

Outcomes: reduction in wound size, percentage wound area reduction (PAR), and time to complete healing.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the patient population, types of wounds, and treatment outcomes. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median, depending on their distribution. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Comparative analyses were performed using t-tests (two-sample unequal variance) on VassarStats to assess differences in treatment outcomes between groups. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Surgical procedure

All patients underwent MMS for the complete excision of NMSCs. The MMS procedure followed standard protocols, involving sequential, layer-by-layer tumor excision with comprehensive microscopic margin control to ensure complete tumor eradication while conserving as much healthy tissue as possible. The surgical technique included a meticulous, layer-by-layer excision with real-time microscopic margin control using frozen sections. Hemostasis was achieved with spot electrocoagulation. The resected tissue was oriented relative to the surgical defect, and a map of the defect was drawn. The frozen section specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, then systematically examined by the surgeon for the presence of tumor. For pain management, a pressure dressing consisting of Vaseline, Telfa, gauze, and paper tape was applied. Patients received local anesthesia using 1% buffered lidocaine with epinephrine (1:100,000). An additional anesthetic was administered as needed. The tumor was excised entirely, and further stages were performed until no tumor cells were identified at the margins.

Wound reconstruction and CAMP application

Following complete tumor removal by MMS, the resulting surgical defects were managed with a standardized wound reconstruction protocol. In all cases, tri-layered amniotic membrane (Q4295 by STABILITYBIOLOGICS®) was applied to the post-surgical wound. The CAMP was administered weekly after the initial surgery. Specific details regarding the preparation and application of the tri-layered amniotic membrane were consistent with the manufacturer’s guidelines and institutional protocols. The graft was anchored with an appropriate fixation method. The triple-layer was placed onto the wound bed or surgical implantation site, ensuring careful preservation of the product and contact with the wound or implant site. The product was rehydrated with saline or bacteriostatic water as necessary. A primary dressing (non-adherent) was applied, followed by a secondary dressing specific to the wound type.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures assessed in this study included:

-

Time to complete healing: Defined as the number of days from the date of MMS until 100% re-epithelialization of the surgical wound, as documented in clinical notes.

-

PAR): Calculated based on serial measurements of wound dimensions at each follow-up visit. The wound volume was determined by multiplying length, width, and depth (cm). Percent area reduction (PAR) was still calculated using surface area measurements obtained at each visit. While volume was recorded for descriptive purposes, PAR calculations used surface area, not volume.

-

PAR was calculated using the formula: PAR = ((Initial Wound Area−Current Wound Area)/ Initial Wound Area) × 100%.

-

Overall wound size reduction: Qualitative assessment and quantitative measurement of the reduction in wound dimensions throughout treatment, contributing to the evaluation of the reconstructive success.

Data collection and statistical analysis

All data were collected from patient medical records. The collected data encompassed a comprehensive range of variables, including:

-

Demographics: sex and date of birth.

-

Medical history: allergies, presence of pacemaker/defibrillator or other implant devices, current chemotherapy, history of chemotherapy in the last 6 months, last menstrual period (LMP), HIV, hepatitis, tuberculosis, recreational drug use, smoking status, alcohol consumption, exercise habits, and general health.

-

Medication and treatment history: surgery history, current medications (including blood thinners), pre-operative antibiotic use, and post-operative antibiotics taken.

-

Dermatologic and tumor characteristics: dermatologic conditions, cutaneous malignancies (type and location), first stage depth of invasion, pathologic pattern (as per biopsy report), perineural invasion, pathologic pattern/ morphology of tumor (as per biopsy report), tumor characteristics (as per first stage), presence of scar tissue, wound location, procedure date, and graft numbers.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics and characteristics of NMSC. Quantitative outcomes, such as time to complete healing and PAR, were analyzed to elucidate the efficacy of the tri-layer amniotic membrane graft in facilitating wound healing and reconstruction. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, detailed statistical analyses involving comparative groups were not the primary focus; instead, the aim was to report observed clinical outcomes.

Results

A total of 46 patients were included in this retrospective study, with their clinical outcomes analyzed following MMS and subsequent wound reconstruction with the CAMP under study. The results for time to complete healing, PAR, and overall wound size reduction are presented below.

Time to complete healing

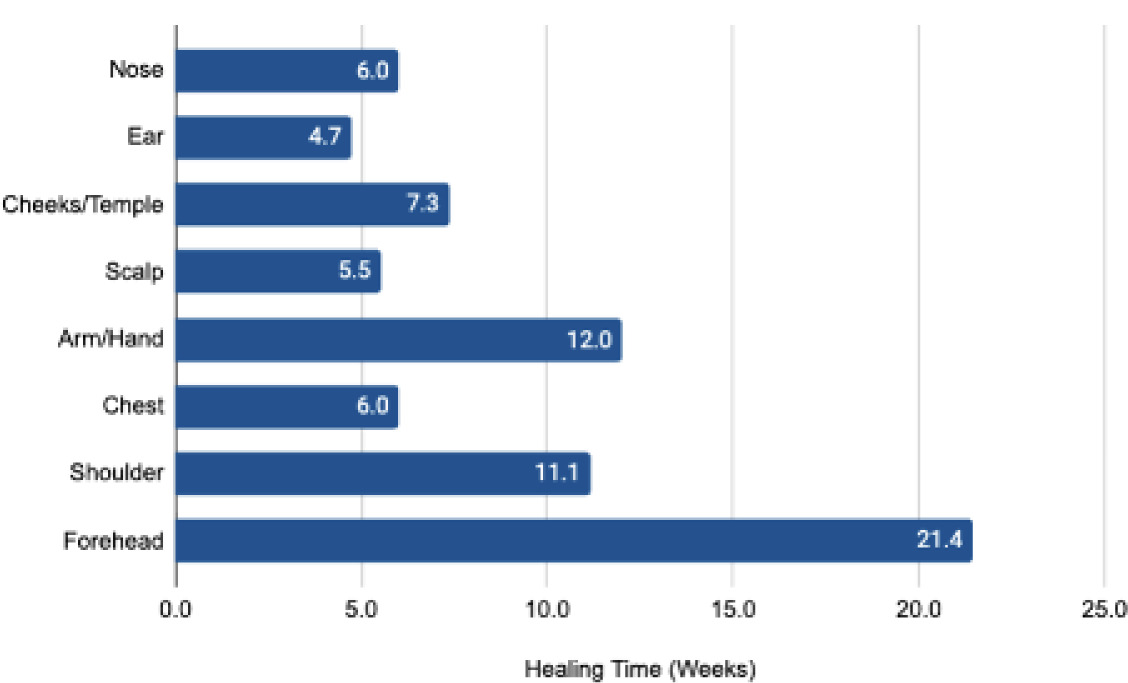

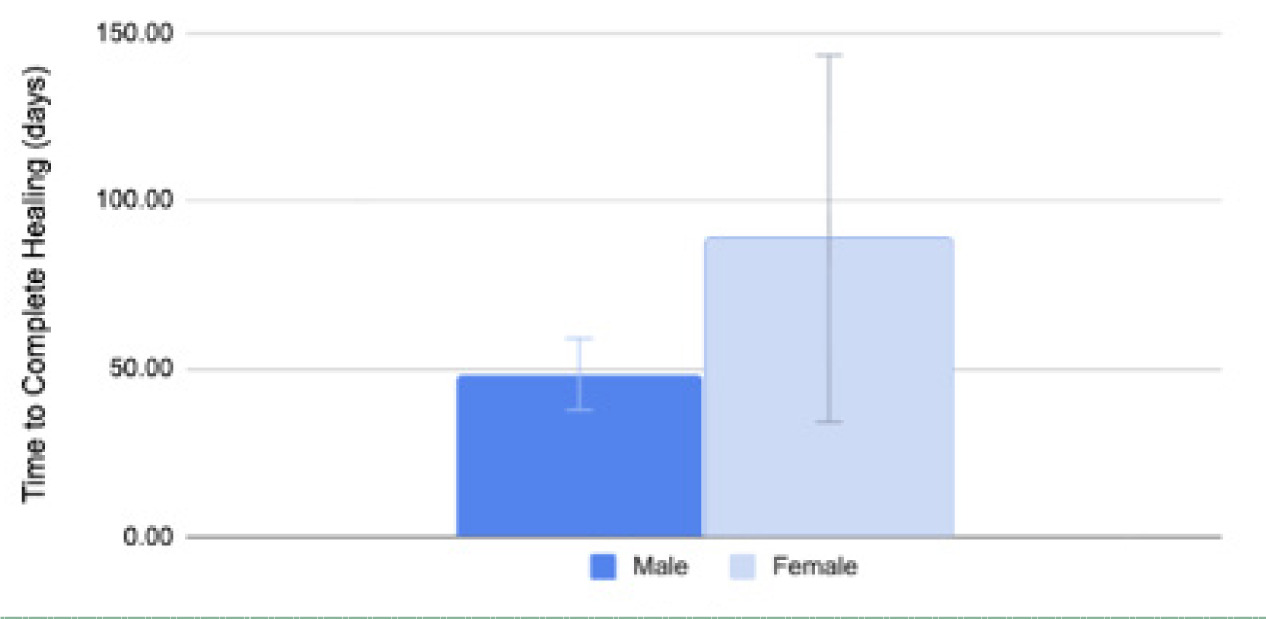

The mean time to complete healing was 8.53±5.73 weeks with a median of 6 weeks. There were nine wounds in males and ten wounds in females that achieved complete closure after treatment with CAMP across various areas (Figures 2 and 3).

FIGURE 2 Mean time to complete healing in weeks across areas treated with CAMP after MMS. Each bar indicates the average number of weeks that were required for complete healing in a specific body location treated with the graft. The forehead shows the longest healing time at 21.4 weeks, followed by the arm/hand at 12.0 weeks, and the shoulder at 11.1 weeks. Other areas, such as the cheeks/temple, chest, nose, scalp, and ear, have shorter healing times, with the ear showing the shortest time of 4.7 weeks.

FIGURE 3 Comparison of the mean time to complete healing between sexes. The bar chart illustrated the mean time to complete healing in days between males (dark blue) and females (light blue) after MMS treatment with CAMP. Males had a mean healing time of 48.43±21.92 days, and females had a mean of 88.80±61.48 days. A significant difference in healing time was not observed between the two groups (p=0.1708, two-tailed).

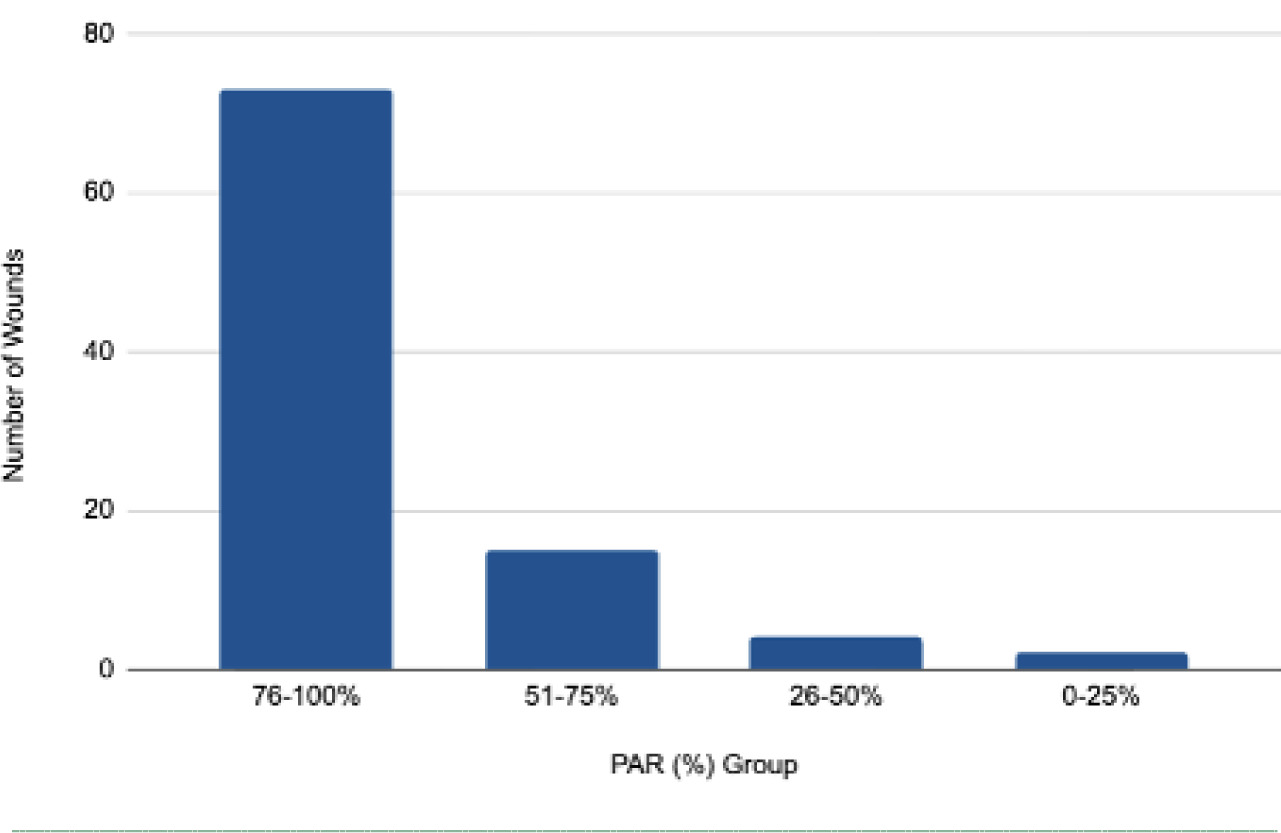

Percentage wound area reduction

Across all types of wounds treated with CAMP, the mean PAR was 84.441±18.96%, with a median of 91.88%. The majority of wounds had a PAR between 76 and 100% after treatment (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4 Frequency distribution of percentage wound area reduction (PAR) after MMS treatment with CAMP. The bar chart illustrates the count of wounds (N=94) grouped based on their measured PAR (%). The graph confirms that the bulk of wounds (≈73) achieved a high PAR in the 76−100% range. Only a small fraction of wounds (≈6) fell into the 0−50% range.

Wound size reduction

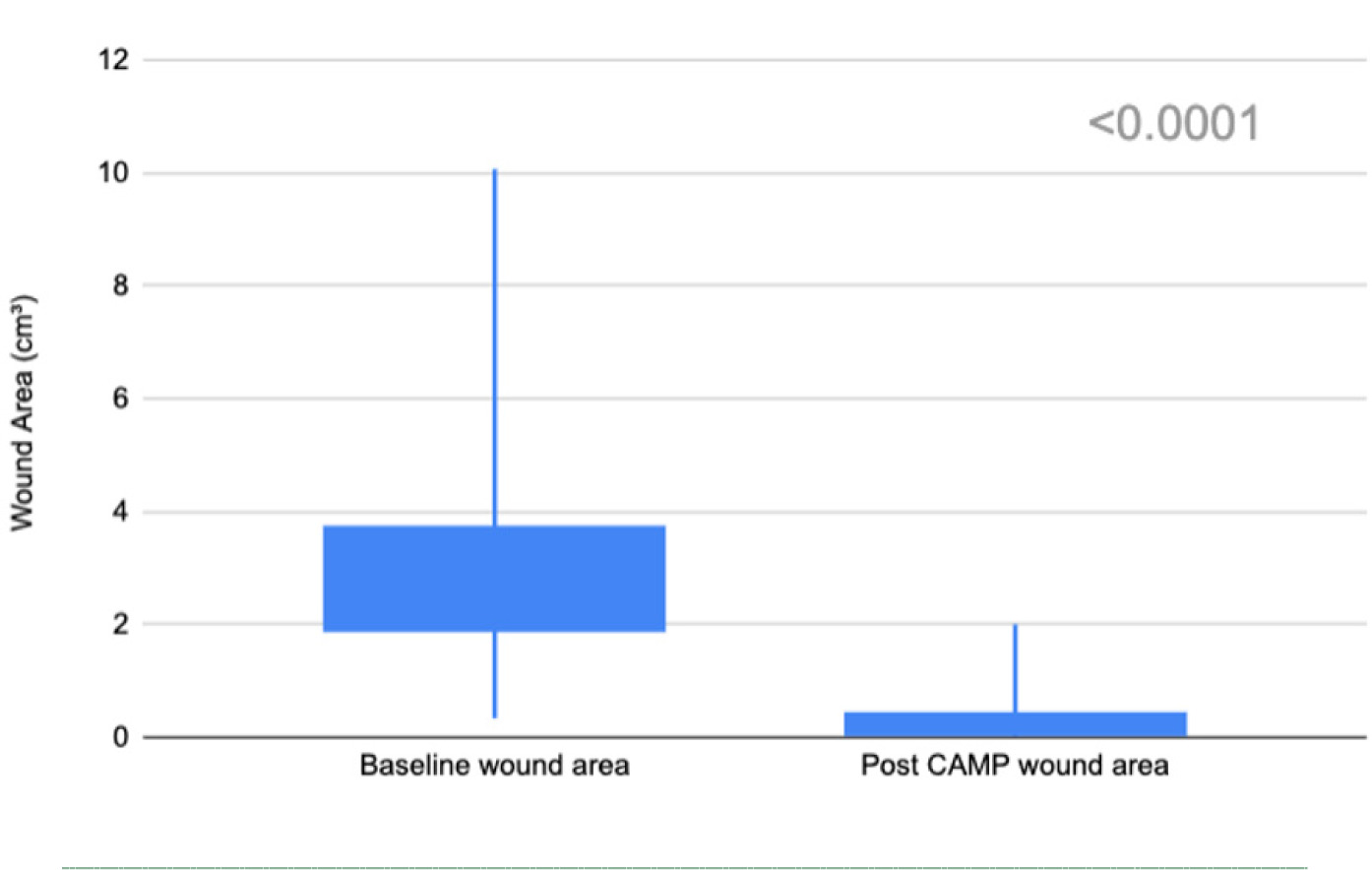

A two-sample paired T-test revealed a significant reduction in wound size after treatment with CAMP (t(94)=16.05, p<0.0001, two-tailed). The mean wound size reduced from 2.77±1.47 cm3 to 0.35±0.43 cm3, with a median decrease from 2.43 cm3 to 0.26 cm3 (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5 Wound size reduction (cm3) after treatment with CAMP. Candlestick plots illustrate the reduction in wound area from the baseline (left) to post-treatment (right). A significant decrease in wound area was observed (p<0.001, two-tailed).

Case studies

Subject 1

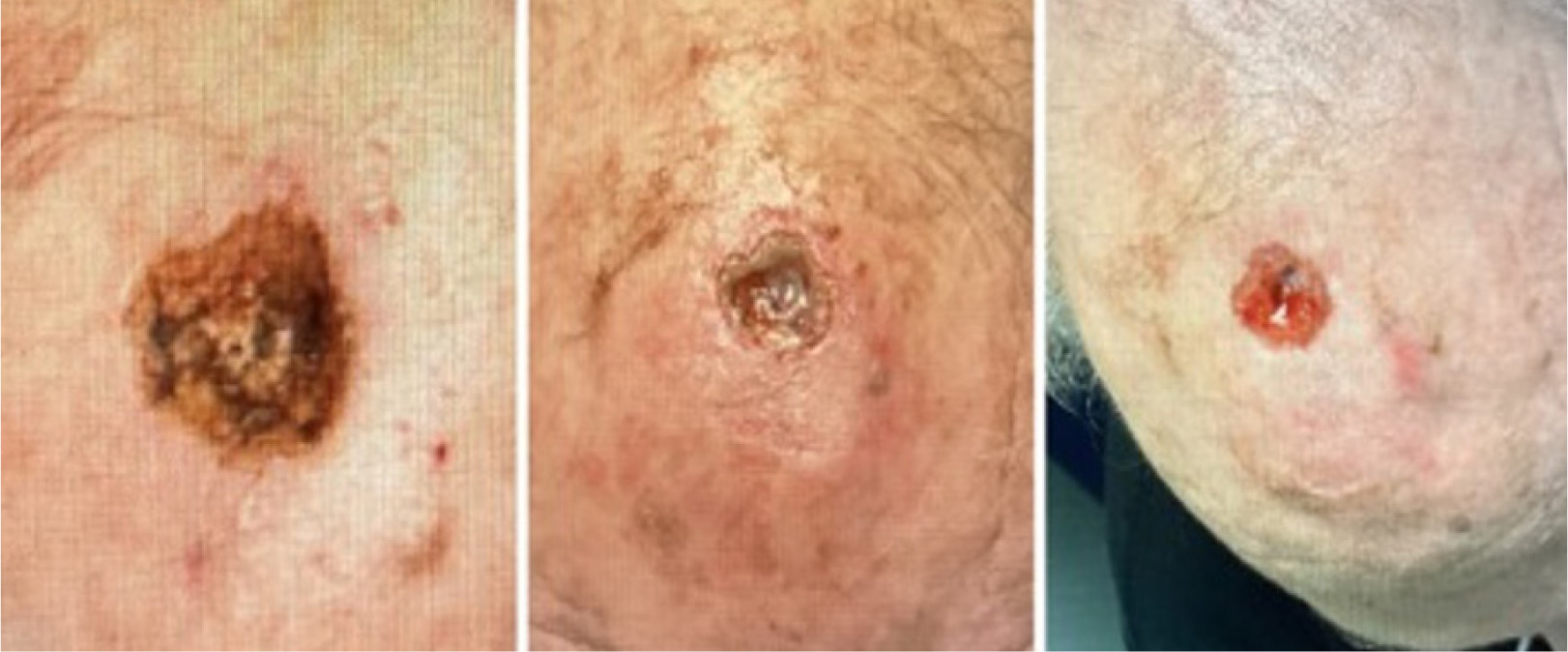

An 80-year-old female with significant cardiovascular and neurological comorbidities, including hypertension, chronic neuropathic pain, and atrial fibrillation, which were managed with apixaban (Eliquis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, New Jersey). She was also on antihypertensives, gabapentin for nerve pain, and simvastatin for hyperlipidemia. Her medical history included sun-damaged skin. She did not smoke or use recreational drugs but reported occasional alcohol consumption. Her allergy profile consisted of a sensitivity to sulfa (sulfonamide antibiotics). Dermatologically, she had a personal and family history of SCC. Her case demonstrated a large post-surgical wound in a cosmetically sensitive region, the nasal area.

On September 9th, the patient underwent MMS for a SCC on the right nasal root. The procedure resulted in a surgical defect with an initial area of 2.43 cm3 (Figure 6, left). On September 26th, the wound area was 0.24 cm3 (Figure 6 middle) and progressed to complete re-epithelialization, 0.00 cm3, by December 12th (Figure 6 right), indicating healing over approximately 13.6 weeks with the application of a CAMP once a week for 3 weeks.

FIGURE 6 Defect of the right nasal root.

Subject 2

An 86-year-old male with a significant medical history of arthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. He was on anticoagulation therapy with apixaban (Eliquis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, New Jersey) for cardiovascular indications. His medical history was positive for extensive sun exposure and a prior MMS for skin cancer. He was an ex-smoker and consumed alcohol regularly. He had no known drug allergies and no history of chemotherapy or immunosuppression. Dermatologically, he had a history of BCC and actinic keratosis. The patient underwent one MMS procedure for a BCC on his left ear. His case demonstrated successful wound healing in an elderly diabetic patient who was taking anticoagulant medication, all of which could affect wound healing. Patients on anticoagulation are at increased risk of postoperative bleeding, hematoma formation, and delayed epithelialization, which can complicate flap or graft survival. In this case, traditional reconstruction options such as a full-thickness skin graft or local flap were considered but not selected due to: (1) exposed auricular cartilage, which increases graft failure risk; (2) the patient’s anticoagulated status, making flap elevation and donor-site bleeding less desirable; and (3) the small, concave ear defect, where CAMP provided a conservative, biologically active alternative that avoids surgical manipulation of cartilage.

On October 17th, 2024, the patient underwent MMS for BCC on the superior helix of the left ear. The procedure resulted in a surgical defect of 2.77 cm3 (Figure 7, left). On October 25th, the wound had reduced to 0.69 cm3 (Figure 7 middle). It progressed to 0.17 cm3 (Figure 7 right) by November 8th, indicating a 93.9% reduction over 3.1 weeks with the application of CAMP once a week for 4 weeks.

FIGURE 7 Defect of the left superior helix of the ear.

Subject 3

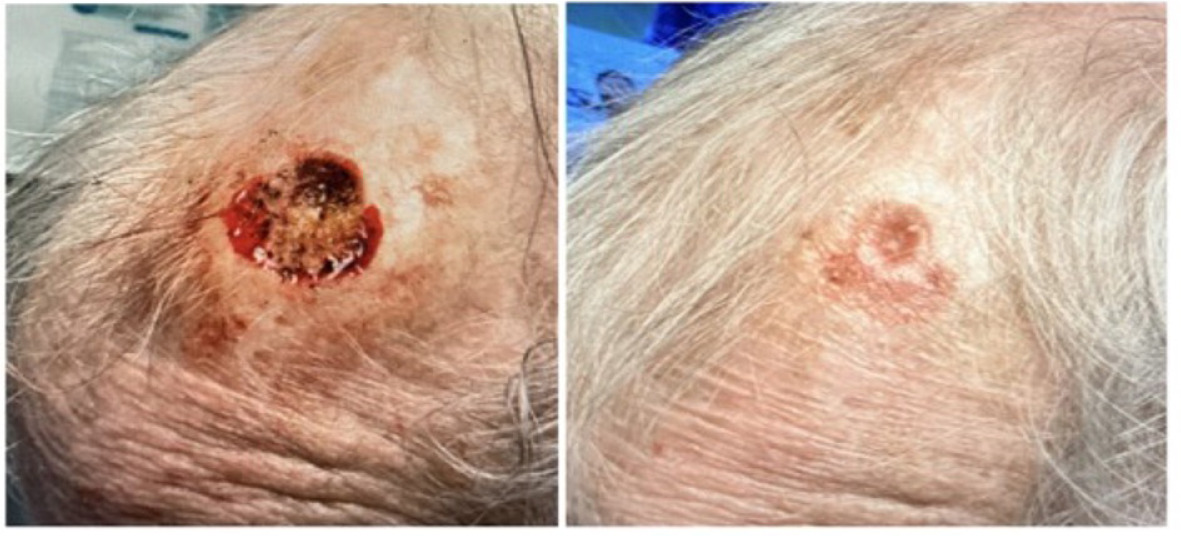

A 78-year-old male with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. He had no history of smoking, blood thinner use, chemotherapy, or immunosuppression. Dermatologically, he had a history of SCC and actinic keratosis. The patient underwent one MMS procedure for an SCC on the scalp. His case demonstrated effective wound healing in a diabetic patient with no smoking habit or use of blood thinners.

On December 12th, 2024, the patient underwent MMS for SCC on the medial frontal scalp. The procedure resulted in a surgical defect with an initial volume of 4.08 cm3 (Figure 8, left). On December 19th, the wound was 0.42 cm3 (Figure 8, middle) and had progressed to 0.31 cm3 by December 26th (Figure 8, right), indicating a 92.4% reduction over 2.0 weeks with the application of CAMP once a week for three weeks. A scalp flap was not used in this patient because local scalp flaps require adequate tissue laxity, which was limited in this patient due to advanced age, prior sun damage, and the defect’s central frontal location. The wound had exposed periosteum with minimal soft-tissue mobility, making flap closure high-risk for tension-related ischemia. CAMP allowed for granulation and epithelialization without flap morbidity.

FIGURE 8 Defect of the medial frontal scalp.

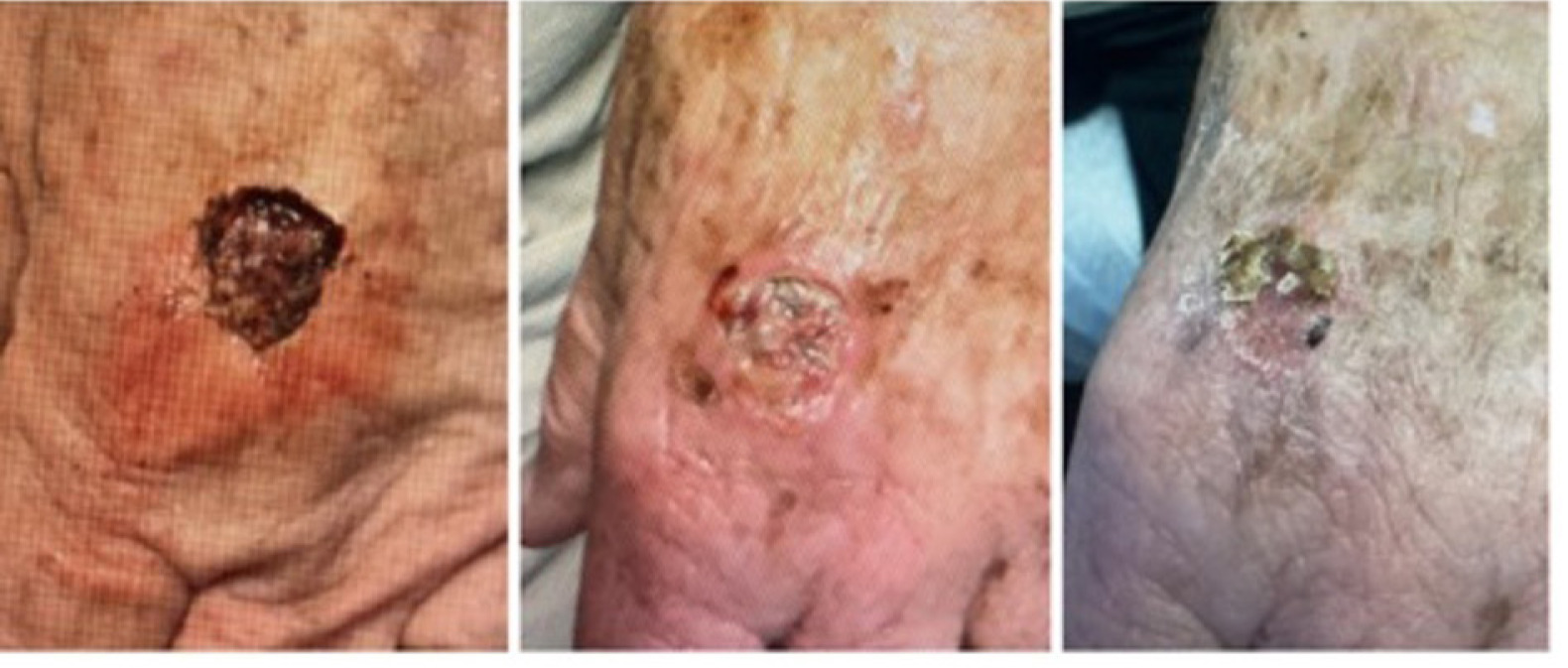

Subject 4

An 83-year-old male on dual anticoagulant/antiplatelet therapy with apixaban (Eliquis) and clopidogrel (Plavix), in addition to aspirin. He was an ex-smoker and a social drinker. He had no known drug allergies and no history of chemotherapy or immunosuppression. Dermatologically, he had a history of SCC and actinic keratosis. His case was particularly notable for demonstrating successful wound healing outcomes on the hand (Figure 9) and scalp (Figure 10) despite a high bleeding risk from his intensive antithrombotic therapy. Given the patient’s dual antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy, traditional options such as split-thickness skin grafting or local flaps carried increased risks of bleeding, hematoma, and graft failure. CAMP provided a noninvasive reconstructive option requiring no additional incisions or harvesting, reducing operative risk while supporting rapid granulation over exposed structures.

FIGURE 9 Defect of the left lateral dorsal hand.

FIGURE 10 Defect of the medial frontal scalp.

On December 5, 2024, the patient underwent MMS for a SCC on the left dorsal hand. The procedure resulted in a surgical defect with an initial volume of 3.52 cm3 (Figure 9, left). By December 12, the volume was 0.55 cm3 (Figure 9, middle) and progressed to complete re-epithelialization by January 9, 2025 (Figure 9, right), indicating healing over approximately 5 weeks with the application of CAMP once a week for 2 weeks.

On January 23rd, 2025, the patient underwent MMS for a SCC on the medial frontal scalp, resulting in a defect of 3.26 cm3 (Figure 10, left). After the initial application of the CAMP, the patient chose to discontinue further use of the graft but continued the follow-up check-ups at the clinic. On February 27th, the wound was completely closed (Figure 10, right). The wound closed in 5 weeks with only one application of the CAMP.

Subject 5

A 71-year-old male with a history of penicillin allergy, gout managed with allopurinol, and hyperlipidemia managed with atorvastatin (Lipitor). His medical history included excessive sun exposure, and he maintained an active lifestyle with regular exercise. He was an ex-smoker and a social drinker. He had no history of blood thinner use, chemotherapy, or immunosuppression. Dermatologically, he had a history of SCC. The patient underwent one MMS procedure for a large SCC on his shoulder. This case demonstrated the rapid healing of a large surface-area wound in a physically active individual in a mobile area of the body.

On September 5th, 2024, the patient underwent MMS for a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the right shoulder. The procedure resulted in a substantial surgical defect of 7.34 cm3 (Figure 11, left). By September 13th, the wound volume had decreased to 2.09 cm3 (Figure 11, middle) and progressed to complete re-epithelialization (Figure 11, right) by December 9th, indicating the healing of a large defect over 13.57 weeks with the application of CAMP once a week for 2 weeks.

FIGURE 11 Defect of the right middle shoulder.

Discussion

This retrospective study evaluated the effectiveness of tri-layered amniotic membrane CAMP for wound reconstruction following MMS for NMSC. The findings demonstrate that across most anatomical sites, CAMP demonstrated a markedly shorter mean time to complete healing compared with traditional secondary intention healing, which is often slow and unpredictable, particularly for deep or extensive surgical defects.28 Although several defects in this series were technically amenable to primary closure, flap, or graft reconstruction, many were managed conservatively due to patient-specific factors including age, comorbidities, anticoagulation, anatomical location, poor tissue mobility, or patient preference to avoid additional surgical manipulation. CAMP allowed for biologically enhanced healing without the morbidity of more invasive procedures.

Historically, large wound cohorts showing healing by secondary intention have reported a mean healing time of approximately 12.3 weeks across various body sites.29 In contrast, the use of a CAMP consistently resulted in faster and more reliable wound closure. For instance, scalp wounds, known to heal slowly due to their gossamer-like periosteum and frequent bone exposure,30,31 showed a mean healing time of only 5.5 weeks with a CAMP (Figure 2). This contrasts sharply with prior literature on secondary intention healing for similar MMS defects on the scalp, where reported mean healing time was often 7-13 weeks or longer, or never when bone is exposed.30,32

Comparable outcomes were also observed in other challenging or highly vascular regions. Wounds on the shoulder and dorsal hand achieved complete closure in an average of 11.1 and 12.0 weeks. Notably, near-complete wound closure was observed in as little as 4.7 weeks in certain cases, such as those involving the ear, further underscoring the regenerative potential of the graft.

The rapid wound closure achieved with the CAMP, even among high-risk patients (including elderly, diabetic, and on anticoagulant therapy individuals), highlights its strong therapeutic advantage. Collectively, these findings suggest that the CAMP offers a superior approach to wound reconstruction compared with secondary intention healing alone, particularly for complex surgical defects or anatomically challenging locations.

Moreover, while the study included both male and female patients, no statistically significant differences in wound healing time or overall outcomes were observed between sexes. Any minor variations in mean healing time were non-significant and are likely attributable to differences in wound size, anatomical location, and patient-specific comorbidities rather than sex itself.33,34 Therefore, the observed therapeutic benefits of CAMP are interpreted as being equally applicable across the sexes.

This study does not include an internal comparator arm, such as secondary intention healing or flap/graft reconstruction. All comparisons are made against historical benchmarks reported in prior literature. Future research should incorporate prospective controlled designs to compare CAMP-assisted healing with standard reconstructive approaches more rigorously.

Limitations

The retrospective nature of this study can introduce biases related to how data were collected and recorded. Additionally, due to the real-world nature of these data, potential confounding factors, such as age, comorbidities, and unknown combined treatment, can coexist. Patient selection bias may also affect the results. The sample size may need to be larger to generalize findings across other types of wounds and patient demographics. Additionally, the sample was drawn from patients only in Florida, United States; therefore, the results may not accurately reflect the broader global population. Lastly, the duration of the treatment with the CAMP varied depending on the requirements of each wound and its baseline size. This heterogeneity may have complicated comparisons and generalizations.

This study includes multiple wounds from the same patient, which violates strict statistical independence assumptions. No multilevel modeling or clustering correction was applied. This should be interpreted as a limitation, and reported outcomes represent wound-level observations rather than patient-level effects.

Conclusion

The findings from this retrospective study indicate a significant efficacy of the tri-layered CAMP for reconstructing post-Mohs surgical defects. The utilization of a CAMP resulted in a statistically significant acceleration of wound closure and substantially reduced mean healing times across diverse anatomical locations compared to established historical metrics for secondary intention healing.