Introduction

The use of dehydrated porcine placental extracellular matrix (PPECM) has recently gained prominence in the treatment of chronic, hard-to-heal wounds, particularly diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) and venous leg ulcers (VLUs). PPECM is characterized by its rich composition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, growth factors, and cytokines that facilitate wound healing processes, including cell migration and angiogenesis. Retrospective reviews and Medicare database analyses have demonstrated improved healing outcomes, reduced healing times, and effective management of bioburden with PPECM compared to standard methods.1-5 These findings position PPECM as a biologically compatible and clinically effective option in chronic wound management, aiding tissue regeneration across complex wound types.

This retrospective study was conducted to evaluate the real-world efficacy of Innovamatrix™, a dehydrated PPECM, in the management of complex chronic wounds that have proven refractory to conventional standard-of-care (SOC) therapies. Through analysis of outcomes in a heterogeneous patient cohort comprising chronic DFUs, VLUs, pressure injuries, and other open wounds of diverse etiologies, durations, and severities, the primary endpoint was to determine rates of complete wound closure. Secondary endpoints included the percent area reduction (PAR) in wound surface area, average number of applications to achieve wound closure, and time to complete closure. Furthermore, this investigation aimed to generate practical, evidence-based insights into the integration of porcine placental membrane allografts within comprehensive, multimodal chronic wound management strategies, thereby contributing to the expanding body of clinical evidence supporting their use in recalcitrant and high-risk wound-healing scenarios.

Methods

Data source and definitions

This investigation used an electronic health record (EHR) database from a multistate network of private wound-care practices across Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas to identify patients treated with Innovamatrix™. Patients included in the analysis received at least one application of a cellular, acellular matrix-like product (CAMP) between 3 January 2018 and 30 June 2025. However, patients receiving Innovamatrix™ were noted to have received the graft between 11 October 2023 and 30 June 2025. Treatment was performed in outpatient private wound care clinics, skilled and long-term nursing facilities, and home settings. An initial case identification was performed using accounts receivable reports to capture relevant International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes, and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Wound types were comprised of chronic DFUs, VLUs, pressure injuries and open wounds. These etiologies were confirmed by cross-referencing the ICD-10 and CPT codes recorded in the accounts receivable data within the EHR. Final wound characteristics, treatment details, healing outcomes and patient demographic information were extracted via manual chart review of the identified records.

All patients included in the study had received at least 30 days of SOC therapy before the first application of the PPECM. During this 30-day period, all wounds demonstrated <50% reduction in surface area, thereby confirming their classification as chronic, non-healing or hard-to-heal wounds. Additionally, every patient satisfied the 2025 Local Coverage Determination (LCD) eligibility requirements for PPECM use, as defined by the applicable Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) for chronic DFUs, VLUs, pressure injuries, and open wounds.6 An application series was defined as one or more consecutive PPECM applications, with no interval exceeding 21 days between applications, for up to 15 applications.

Chronic wounds were classified into four mutually exclusive categories for this analysis. DFUs were defined as full-thickness wounds located on or distal to the ankle in patients with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (type 1 or type 2). VLUs were defined as full-thickness wounds of the lower extremity in patients with documented venous insufficiency, confirmed by duplex ultrasonography demonstrating venous reflux exceeding 0.5 seconds. Pressure injuries were defined as full-thickness wounds situated over bony prominences or resulting from sustained pressure from a medical device, regardless of anatomic location. The category of open wounds encompassed all remaining full-thickness chronic wounds of surgical, traumatic, or other etiologies (diagnosed as “open wound”) that did not fulfill the diagnostic criteria for DFUs, VLUs, or pressure injuries. All wounds included in the analysis met the accepted definition of chronicity, defined as consistent SOC therapy for at least 30 days, accompanied by <50% PAR during the 30-day pre-treatment period.

Wound surface area was measured in square centimeters (cm2) using the standardized ruler-based method of greatest length x greatest width, applied uniformly across all participating centers. Baseline measurements were taken at the time of the first PPECM application. Final measurements were recorded either at the last PPECM application or within 14 days thereafter. Complete wound closure was defined as 99.99–100% PAR with full re-epithelialization, as documented in the EHR. This stringent threshold was adopted to ensure consistency, as clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) commonly recorded the minimal residual wound area as 0.01 cm2 during follow-up visits once clinical healing had been achieved. Patients whose wounds reached 0.01 cm2 continued to be monitored at the discretion of the treating clinician to confirm wound closure. Definitive healing was documented only when the wound area was recorded as 0.0 cm2 prior to discharge from wound treatment services.

Design and procedures

The primary objective was to determine the rate of complete wound closure among patients treated with a PPECM. The secondary objective was to quantify PAR from baseline to final assessment in wounds receiving one or more PPECM applications, determine the average number of PPECM applications required to achieve complete closure, and determine the average time to closure for healed wounds. The study was privately funded, with no financial support, sponsorship or grants from the device manufacturer or any commercial entity. Reimbursement for Innovamatrix™ applications was provided in accordance with applicable LCD and MAC policies throughout the study period. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Sterling Institutional Review Board (IRB ID: 15324).

All PPECM applications were performed by wound medicine clinicians in strict accordance with established institutional protocols governing the use of CAMPs. Innovamatrix™ is a dehydrated multilayer porcine placental extracellular matrix derived from combined amnion-chorion ECM, analogous to human amnion-chorion membrane products in structure and composition, providing a scaffold rich in ECM proteins, growth factors, and cytokines to support wound healing. Innovamatrix™ was applied only after comprehensive optimization of SOC measures during a minimum 30-day run-in period. SOC refers to pre-treatment optimized therapies (e.g., debridement, offloading) that failed to achieve ≥50% PAR; during PPECM treatment, it denotes continued comprehensive adjunctive measures integrated with graft application. Previously failed SOC therapies included, but were not limited to, aggressive debridement, infection management, offloading or compression therapy, and nutritional optimization. For VLUs, referrals to vascular surgeons for venous ablation were made at the provider’s discretion if reflux disease was identified via duplex ultrasonography. Arterial circulation was optimized prior to PPECM application in accordance with LCD guidelines. Pressure injuries included stages 2 through 4; osteomyelitis, if present, was treated prior to or concurrently with PPECM applications. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) was employed at the provider’s discretion prior to or in combination with PPECM applications. Required elements of SOC included aggressive sharps and/or ultrasonic debridement, confirmation of adequate tissue perfusion, complete eradication of infection and devitalized tissue, and implementation of etiology-specific offloading (for DFUs, pressure injuries, and open wounds if applicable) or multilayer compression therapy (for VLUs and open wounds if applicable). Nutritional status was systematically evaluated, and counseling and therapeutic intervention provided for identified deficiencies. Smoking cessation counseling was delivered to all active smokers. Patients exhibiting poor glycemic control received diabetes education, pharmacological optimization, and referral to primary care or endocrinology services as appropriate. Only wounds that remained within the classification of non-healing despite this rigorous pretreatment regimen were deemed eligible for PPECM application.

Primary dressings were selected for their ability to secure the PPECM in direct contact with the wound bed, and secondary dressings were selected based on exudate level to maintain an appropriately moist wound environment. Etiology-specific pressure redistribution and offloading measures were implemented and individualized according to wound type and anatomic location. Plantar DFUs were managed with total-contact casting, removable cast walkers, therapeutic depth-inlay footwear, or custom orthotic devices as clinically indicated. Pelvic pressure injuries were managed with low-air-loss and/or alternating-pressure mattresses, specialized orthotic cushions, strict turning/ repositioning schedules, and provider-directed limitations on sitting duration. Heel and other lower-extremity pressure injuries were treated with heel-protection devices, suspension boots, or pressure-redistributing cushions as appropriate. VLUs received sustained multilayer compression therapy (typically 30–40 mmHg) to counteract ambulatory venous hypertension. All adjunctive measures were continued throughout the PPECM treatment course.

Secondary dressings were changed 2-3 times per week based on exudate volume, while the primary contact dressing and PPECM were generally left in place for approximately 7 days to optimize graft integration. Patients were evaluated at weekly clinic visits, during which, selective sharp or ultrasonic debridement was performed as indicated, wound measurements were recorded, and a new PPEMC was applied. This treatment cycle was repeated for up to 15 applications or until complete wound closure was documented, whichever occurred first.

Outcome measures

The primary endpoint of this retrospective analysis was the proportion of wounds achieving complete closure, defined as full re-epithelialization with 99.99-100% PAR, following treatment with Innovamatrix™. Secondary endpoints included the mean and median number of PPEMC applications required to achieve complete closure, PAR after each sequential application, and average time to heal for wounds achieving complete closure. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics were summarized descriptively. Pertinent comorbidities were identified and abstracted via manual chart review, with selection focused on conditions most relevant to chronic wound pathogenesis and healing potential in advanced wound medicine practice.

Sample selection

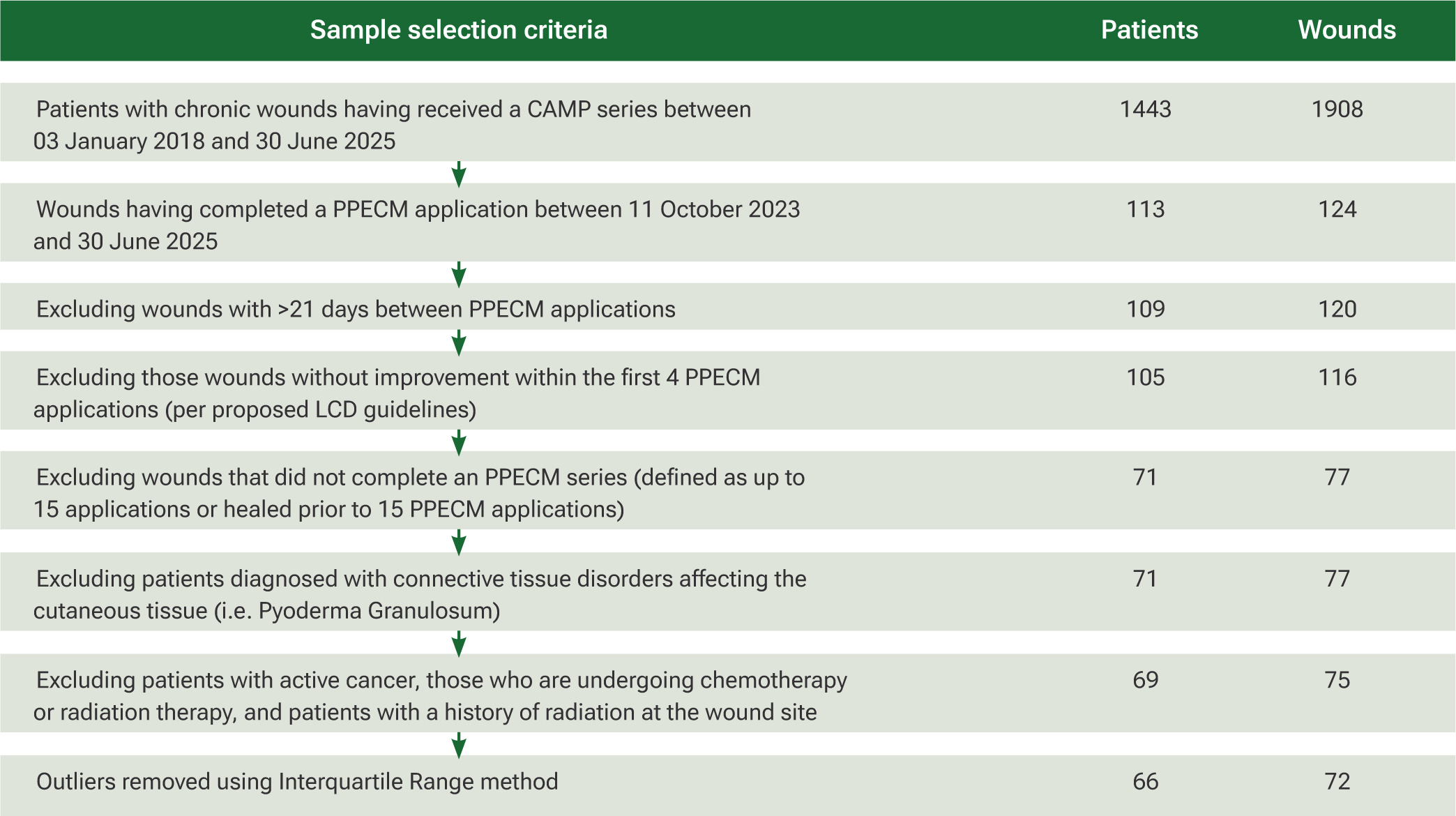

A comprehensive dataset search was conducted by initially identifying all patients who received any CAMPs between 3 January 2018 and 30 June 2025. The cohort was subsequently restricted to patients treated exclusively with Innovamatrix™ during the period of 11 October 2023 to 30 June 2025, using specific CPT codes. ICD-10 diagnosis codes were then applied to select patients whose wounds corresponded to one of four prespecified etiologies: DFUs, VLUs, pressure injuries, and open wounds. To maintain fidelity to the intended treatment protocol, patients with an interval greater than 21 days between any two consecutive PPECM applications were excluded, as this violated the definition of a continuous application series. Patients with systemic or localized connective-tissue disorders known to impair cutaneous healing (e.g. Raynaud phenomenon, calciphylaxis, pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis, etc.) were identified through chart review and excluded. Similarly, patients actively receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy, or those with a history of prior radiation at the wound site, were excluded. The stepwise patient selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1 Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flowchart showing sample selection criteria. Abbreviations: CAMP, cellular, acellular matrix-like product; LCD, Local Coverage Determination; PPECM, porcine placental extracellular matrix

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for PAR using serial wound surface area measurements obtained immediately prior to each Innovamatrix™ application and extending through 14 days following the final application in the series. All descriptive summaries—including patient demographics, baseline clinical and wound characteristics, mean wound area after each application, and cumulative PAR—were generated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

Inferential statistical analyses compared baseline wound surface area (measured immediately before the first PPECM application) with final wound surface area (measured at the final application or within 14 days thereafter). Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0.2.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and Python 3.12 with NumPy and SciPy libraries (Python Software Foundation). Pre- and post-treatment mean wound areas were compared using paired-samples t tests; effect size was reported as Cohen’s d. The linear association between initial wound area and the number of PPECM applications required for closure was assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r).

Time-to-event analysis was conducted for all wounds achieving complete closure. A Kaplan-Meier curve was constructed to estimate the probability of healing over time, with the event defined as complete re-epithelialization documented at the final application or within 14 days thereafter; wounds not achieving closure were censored at the last recorded visit.

All tests were two-tailed, with statistical significance set at p<0.05; 95% confidence intervals were reported for primary comparisons. Before inferential testing, extreme outliers were identified and removed using the interquartile range (IQR) method. Values below Q1 – 1.5 x IQR or above Q3 + 1.5 x IQR for wound area for PAR were excluded, providing a robust, non-parametric approach suitable for the typically skewed distribution observed in wound-healing datasets.

Results

Patient and wound characteristics

The study sample included 66 patients with a mean age of 70.02 years (standard deviation (SD)=13.94) with approximately 72.2% were aged 65 years or older. The most prevalent comorbidities amongst the sample were hypertension (78.79%), diabetes mellitus (50%; mean HbA1c 7.07%, SD=1.4), and hyperlipidemia (40.91%). The racial distribution was predominantly White (68.18%) and Black (30.3%) individuals. The gender distribution of the cohort included 34 males (51.52%) and 32 females (48.48%). Only 16.67% of patients reported current nicotine use during the treatment period.

A total of 72 wounds were reviewed for analysis, comprising 38 (52.78%) open wounds, 18 (25%) DFUs, 12 (16.67%) pressure ulcers, and 4 (5.56%) VLUs. Most wounds (73.61%) were treated in a private outpatient clinic, whereas 20.83% were managed at home, and 5.56% were treated in skilled nursing or long-term care facilities. Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1, and wound characteristics are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 1 Patient demographics

| All patients (n=66) | DFU patients (n=17) | VLU patients (n=3) | PI patients (n=11) | OW patients (n=36) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private clinic | 49 (74.24) | 13 (76.47) | 2 (66.67) | 6 (54.55) | 28 (77.78) |

| Home | 13 (19.7) | 2 (11.76) | 1 (33.33) | 4 (36.36) | 7 (19.44) |

| Nursing home | 4 (6.06) | 2 (11.76) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.09) | 1 (2.78) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 70.02 (13.94) | 67.18 (8.52) | 72.33 (10.21) | 66.09 (21.35) | 72.42 (13.3) |

| >65, No. (%) | 48 (72.2) | 12 (70.59) | 25 (69.44) | 6 (54.55) | 2 (66.67) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||

| Male | 34 (51.52) | 11 (64.71) | 1 (33.33) | 9 (81.82) | 13 (36.11) |

| Female | 32 (48.48) | 6 (35.29) | 2 (66.67) | 2 (18.18) | 23 (63.89) |

| Race or Ethnicity, No. (%) | |||||

| Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Black | 20 (30.3) | 6 (35.29) | 1 (33.33) | 6 (54.55) | 7 (19.44) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Native American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.52) | 1 (5.88) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| White | 45 (68.18) | 10 (58.82) | 2 (66.67) | 5 (45.45) | 29 (80.56) |

| Current nicotine use, No. (%) | 11 (16.67) | 2 (11.76) | 0 (0) | 2 (18.18) | 7 (19.44) |

| Comorbidities, No. (%) | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (50.00) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 5 (45.45) | 12 (33.33) |

| HbA1C mean (SD) | 7.067 (1.40) | 7.36 (1.57) | 5.2 (0) | 7.4 (0) | 6.81 (1.13) |

| Hypertension | 52 (78.79) | 14 (82.35) | 2 (66.67) | 8 (72.73) | 29 (80.56) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 27 (40.91) | 7 (41.18) | 0 (0) | 4 (36.36) | 16 (44.44) |

| Chronic atrial fibrillation | 5 (7.58) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.09) | 4 (11.11) |

| Congestive heart failure | 10 (15.15) | 2 (11.76) | 2 (66.67) | 2 (18.18) | 4 (11.11) |

| Chronic renal disease | 15 (22.73) | 6 (35.29) | 1 (33.33) | 2 (18.18) | 7 (19.44) |

| Anemia | 16 (24.24) | 5 (29.41) | 0 (0) | 4 (36.36) | 8 (22.22) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 (12.12) | 3 (17.65) | 0 (0) | 3 (27.27) | 2 (5.56) |

| Spinal cord injury | 12 (18.18) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (72.73) | 4 (11.11) |

| Cancer | 8 (12.12) | 1 (5.88) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.09) | 6 (16.67) |

Table showing patient demographic characteristics. Abbreviations: DFU, diabetic foot ulcer; HbA1C, hemoglobin A1C; OW, open wound; PI, pressure injury; SD, standard deviation; VLU, venous leg ulcer. Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding and patients being treated for multiple wound etiologies.

TABLE 2 Wound characteristics

| All wounds (n=72) | DFU (n=18) | VLU (n=4) | PI (n=12) | OW (n=38) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Setting, No. (%) | |||||

| Private Clinic | 53 (73.61) | 14 (77.78) | 3 (75) | 7 (58.33) | 29 (76.32) |

| Home | 15 (20.83) | 2 (11.11) | 1 (25) | 4 (33.33) | 8 (21.05) |

| Nursing Home | 4 (5.56) | 2 (11.11) | 0(0) | 1 (8.33) | 1 (2.63) |

Table showing wound characteristics. Abbreviations: DFU, diabetic foot ulcer; OW, open wound; PI, pressure injury; VLU, venous leg ulcer. Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

Area reduction

The mean PAR increased progressively with successive applications of the Innovamatrix™ series, cumulating in an overall mean PAR of 85.92%. A pronounced decline in mean wound area was observed through the first five PPECM applications, followed by a minor transient increase of 0.08 cm2 thereafter, before resuming a moderate sustained reduction. When stratified by etiology, all wound types showed a decrease in mean surface area over the treatment course. DFUs and chronic open wounds displayed the most consistent progressive decline following each application. In contrast, VLUs showed a modest rebound in mean area after the ninth application, whereas pressure injuries demonstrated a more pronounced transient increase of approximately 1 cm2 after the fifth application. Analogous patterns were observed in etiology-specific PAR trajectories. Despite these intermittent variations, all wound types ultimately achieved substantial and clinically meaningful reductions in wound area by the conclusion of the treatment regimen.

DFUs (n=18) initially presented with a mean baseline area of 5.4 cm2 (SD 6.98), which reduced to 1.59 cm2 (SD 4.49) after a mean of 9.5 (SD 3.33) PPECM applications, corresponding to a PAR of 85.33%. Despite the limited sample size (n=4), VLUs exhibited the largest initial mean wound area of 21.64 cm2 (SD 20) and achieved the greatest absolute area reduction, closing to 6.28 cm2 (SD 10.96) and yielding a PAR of 81.63%. Pressure injuries (n=12) had an initial mean area of 7.5 cm2 (SD 8), decreasing to 2.2 cm2 (SD 3.87) after an average of 9.5 (SD 1.93) applications, yielding a PAR of 80.15%. Chronic open wounds (n=38), the largest subgroup, demonstrated a mean initial area of 10.32 cm2 (SD 15.21), which decreased to 2.03 cm2 (SD 6.58) after a mean of 6.79 (SD 4.42) applications, yielding a final PAR of 86.91%. Across all wound etiologies, the median number of PPECM applications ranged from 6–11.5. Mean wound area per application is presented in Table 3, and the mean PAR per application is displayed in Table 4.

TABLE 3 Average area per application

| All wounds (n=72) | DFU (n=18) | VLU (n=4) | PI (n=12) | OW (n=38) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area after application, No. (%) | |||||

| Initial Area | 9.75 (15.97) | 5.4 (6.98) | 21.64 (20) | 7.5 (8) | 10.32(15.21) |

| Application #1 | 8.70 (17.38) | 4.57 (6.66) | 18.97(19.19) | 5.96 (8.01) | 8.68 (15.97) |

| Application #2 | 7.01 (14.28) | 3.95 (5.95) | 16.54 (19.16) | 4.58 (6.37) | 6.84 (12.95) |

| Application #3 | 5.83 (12.67) | 3.2 (4.77) | 15.43 (17.54) | 4.04 (5.78) | 5.56 (11.62) |

| Application #4 | 5.17 (11.41) | 2.61 (4.32) | 14.23 (17.39) | 3.58 (5.73) | 4.33 (9.91) |

| Application #5 | 4.74 (11.13) | 2.66 (4.58) | 14.18 (16.34) | 3.32 (4.8) | 3.96 (9.8) |

| Application #6 | 4.82 (11.63) | 2.46 (5.16) | 11.68 (15.56) | 4.32 (9.99) | 3.39 (9.06) |

| Application #7 | 4.28 (10.90) | 2.23 (4.96) | 9.51 (14.59) | 3.48 (8.02) | 3.23 (9.14) |

| Application #8 | 3.94 (9.40) | 2.18 (4.75) | 9.27 (14.67) | 3.06 (5.8) | 2.92 (8.13) |

| Application #9 | 3.57 (8.68) | 1.89 (4.52) | 8.3 (14.18) | 2.95 (5.4) | 2.53 (7.03) |

| Application #10 | 3.41 (8.62) | 1.7 (4.32) | 8.48 (14.09) | 2.92 (5.41) | 2.46 (6.99) |

| Application #11 | 3.34 (8.53) | 1.71 (4.33) | 9.05 (13.92) | 2.83 (5.45) | 2.36 (6.87) |

| Application #12 | 3.17 (8.50) | 1.68 (4.33) | 8.26 (14.21) | 2.83 (5.45) | 2.3 (6.84) |

| Application #13 | 3.15 (8.49) | 1.65 (4.34) | 8.48 (14.1) | 2.83 (5.45) | 2.26 (6.82) |

| Application #14 | 3.00 (8.44) | 1.64 (4.35) | 8.48 (14.1) | 2.83 (5.45) | 2.13 (6.76) |

| Application #15 | 2.58 (7.50) | 1.59 (4.49) | 6.28 (10.96) | 2.2 (3.87) | 2.03 (6.58) |

| No. of applications received, mean (SD), median | 8.19 (4.01), 10 | 9.5 (3.33), 10 | 11.75 (2.06), 11.5 | 9.5 (1.93), 10 | 6.79 (4.42), 6 |

Table showing average area after each PPECM application. Abbreviations: DFU, diabetic foot ulcer; OW, open wound; PI, pressure injury; PPECM, porcine placental extracellular matrix; SD, standard deviation; VLU, venous leg ulcer

TABLE 4 Average PAR per application

| All wounds (n=72) | DFU (n=18) | VLU (n=4) | PI (n=12) | OW (n=38) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAR after application, No. (%) | |||||

| Initial PAR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Application #1 | 27.88 (30.48) | 21.71 (27.61) | 19.67 (20.49) | 26.8 (18.72) | 30.45 (31.33) |

| Application #2 | 41.82 (34.92) | 37.1 (31.24) | 30.33 (30.7) | 44 (25) | 46.01 (36.09) |

| Application #3 | 54.45 (33.16) | 51.19 (28.07) | 37.37 (26.09) | 54.42 (28.57) | 57.89 (35.52) |

| Application #4 | 64.38 (32.22) | 60.1 (30.14) | 44.3 (26.94) | 62.97 (29.88) | 69.14 (30.87) |

| Application #5 | 65.55 (35.95) | 57.59 (33.87) | 49.92 (22.94) | 63.06 (37.93) | 71.15 (32.99) |

| Application #6 | 69.2 (33.55) | 64.49 (28.56) | 55.4 (24.4) | 64.68 (35.41) | 76.26 (32.75) |

| Application #7 | 75.76 (29.12) | 69.44 (31.09) | 65.98 (23.64) | 71.28 (29.84) | 79.03 (29.69) |

| Application #8 | 74.81 (30.93) | 70.59 (30.93) | 69.74 (25.2) | 72.63 (32.53) | 80.34 (29.36) |

| Application #9 | 79.13 (26.4) | 76.84 (25.92) | 76.02 (26.09) | 73.38 (31.91) | 83.44 (25.5) |

| Application #10 | 81.5 (25.32) | 80.29 (23.1) | 75.56 (25.79) | 73.91 (32.41) | 83.37 (28.27) |

| Application #11 | 82.39 (24.77) | 81.02 (23.46) | 71.53 (26.5) | 76.24 (32.66) | 84.07 (27.89) |

| Application #12 | 83.78 (24.21) | 81.51 (23.32) | 76.95 (27.05) | 76.3 (32.7) | 84.41 (27.71) |

| Application #13 | 84.15 (24.13) | 82.67 (23.36) | 75.63 (26.47) | 76.31 (32.7) | 84.91 (27.6) |

| Application #14 | 85.01 (23.98) | 83.26 (23.55) | 75.63 (26.47) | 76.31 (32.7) | 85.66 (27.47) |

| Application #15 | 85.92 (23.57) | 85.33 (24.41) | 81.63 (21.08) | 80.15 (25.55) | 86.91 (23.14) |

| No. of applications received, mean (SD), median | 8.19 (4.01), 10 | 9.5 (3.33), 10 | 11.75 (2.06), 11.5 | 9.5 (1.93), 10 | 6.79 (4.42), 6 |

Table showing PAR after each PPECM application. Abbreviations: DFU, diabetic foot ulcer; OW, open wound; PAR, percentage area reduction; PI, pressure injury; PPECM, porcine placental extracellular matrix; SD, standard deviation; VLU, venous leg ulcer

Healed wound characteristics

A total of 46 wounds (63.89% of the cohort) achieved complete re-epithelialization with PPECM treatment. These wounds were comprised of 11 DFUs (61.11% of all DFUs), 6 pressure injuries (50% of all pressure injuries), and 29 open wounds (76.31% of all open wounds). No VLUs reached complete closure; interpretation of VLU outcomes is limited by the small sample size (n=4), precluding meaningful subgroup analysis for this etiology. Among all healed chronic wounds, the overall mean ± SD of PPECM applications required for complete closure was 6.28 ±3.58 (median 6). When stratified by wound etiology, healed pressure injuries required the highest mean number of applications (8.83 ± 2.64; median 8), followed by DFUs (8.09 ± 3.36; median 8). Chronic open wounds demonstrated the most rapid healing trajectory, achieving complete closure after the fewest applications (5.07 ± 3.33, median 4). All wounds, including those of surgical or traumatic etiology, were chronic (demonstrating <50% PAR after ≥30 days of SOC) and not acute.

Overall, the majority of wounds that ultimately healed achieved closure by the sixth Innovamatrix™ application, after which the cumulative healing rate plateaued. The cumulative proportion of healed wounds stabilized after the 10th application. When stratified by etiology, chronic open wounds exhibited the steepest cumulative healing trajectory with successive applications, indicating more rapid closure than other wound types. The distribution of healed wounds per PPECM application is displayed in Table 5, while the cumulative number and proportion of healed wounds by etiology are summarized in Table 6.

TABLE 5 Healed wound characteristics

| All wounds (n=46) | DFU (n=11) | PI (n=6) | OW (n=29) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healed after application, No. (%) | |||||

| Application #1 | 2 (4.35) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Application #2 | 8 (17.39) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (27.59) | |

| Application #3 | 13 (28.26) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (44.83) | |

| Application #4 | 18 (39.13) | 2 (18.18) | 0 (0) | 16 (55.17) | |

| Application #5 | 21 (45.65) | 4 (36.36) | 0 (0) | 17 (58.62) | |

| Application #6 | 25 (54.35) | 4 (36.36) | 1 (16.67) | 20 (68.97) | |

| Application #7 | 29 (63.04) | 5 (45.45) | 2 (33.33) | 22 (75.86) | |

| Application #8 | 34 (73.91) | 6 (54.55) | 4 (66.67) | 24 (82.76) | |

| Application #9 | 35 (76.09) | 6 (54.55) | 4 (66.67) | 25 (86.21) | |

| Application #10 | 40 (86.96) | 8 (72.73) | 4 (66.67) | 28 (96.55) | |

| Application #11 | 43 (93.48) | 10 (90.91) | 5 (83.33) | 28 (96.55) | |

| Application #12 | 43 (93.48) | 10 (90.91) | 5 (83.33) | 28 (96.55) | |

| Application #13 | 44 (95.65) | 10 (90.91) | 6 (100) | 28 (96.55) | |

| Application #14 | 46 (100) | 11 (100) | 6 (100) | 29 (100) | |

| Application #15 | 46 (100) | 11 (100) | 6 (100) | 29 (100) | |

| No. of applications to achieve closure, mean (SD), median | 6.28 (3.58), 6 | 8.09 (3.36), 8 | 8.83 (2.64), 8 | 5.07 (3.33), 4 | |

Table showing healed wound characteristics. Abbreviations: DFU, diabetic foot ulcer; OW, open wound; PI, pressure injury; SD, standard deviation; VLU venous leg ulcer

TABLE 6 PPECM characteristicsa

| All wounds | DFU | VLU | PI | OW | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total wounds no. (%) | Total healed, no. (%) | Total DFUs no. (%) | Total healed, no. (%) | Total VLUs no. (%) | Total healed, no. (%) | Total PIs, no. (%) | Total healed, no. (%) | Total OWs, no. (%) |

Total healed, no. (%) |

| 72 (100.00) | 46 (63.89) | 18 (25.00) |

11 (61.11) |

4 (5.55) |

0 (0) |

12 (16.67) | 6 (50) |

38 (52.78) | 29 (76.31) |

Includes healed characteristics for Innovamatrix™ for each etiology. Abbreviations: DFU, diabetic foot ulcer; OW, open wound; PI, pressure injury; PPECM, porcine placental extracellular matrix; VLU venous leg ulcer. aIncludes healed characteristics for Innovamatrix™ for each etiology. Percentages displayed are the healed percentage of the individual etiology type.

Inferential statistics

A paired samples t-test was conducted to compare baseline and final wound surface areas across the entire cohort following treatment with the Innovamatrix™ series, as shown in Table 7. The analysis revealed a statistically significant reduction in wound area (t(71)=10.47, p<0.001), accompanied by a moderate-to-large effect size (Cohen’s d=0.65), indicating a clinically meaningful treatment response for the whole population, as summarized in Table 8. Statistical power was limited by small subgroup sizes, particularly for VLUs and pressure injuries. When examined by wound etiology, both DFUs and chronic open wounds demonstrated statistically significant reductions in surface area (DFUs, t(17)=2.55, p<0.001; chronic open wounds, t(37)=13.49, p<0.001), with a large (Cohen’s d>1.0) and moderate (Cohen’s d=0.60) effect sizes, respectively. Pressure injuries showed a large effect size (Cohen’s d=0.89), consistent with a substantial clinical response, although statistical significance was not achieved (t(11) = 7.46, p<0.01), most likely due to limited statistical power. Similarly, VLUs exhibited a large effect size (Cohen’s d>1.0) despite failing to reach statistical significance (t(3)=10.83, p=0.06), a finding attributable to the small sample size (n=4). Collectively, these results suggest that the lack of statistical significance in pressure injuries and VLUs reflects type II error rather than an absence of therapeutic benefit, with effect-size estimates supporting clinically important reduction in surface area across all etiologies.

TABLE 7 Results of the paired samples t-test comparing initial wound area and wound area after the last PPECM application

| Paired differences | P value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI of difference | |||||||||

| M | SD | SEM | Lower | Upper | t | df | 1-sided | 2-sided | |

| All | 7.17 | 10.95 | 1.29 | 4.60 | 9.74 | ||||

| DFU | 3.25 | 2.55 | 0.60 | 1.99 | 4.52 | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| VLU | 16.57 | 10.83 | 5.42 | -0.67 | 33.81 | 3.06 | 3 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| PI | 6.78 | 7.64 | 2.21 | 1.92 | 11.63 | 3.07 | 11 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| OW | 8.16 | 13.49 | 2.19 | 3.72 | 12.59 | 3.73 | 37 | <.001 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; df, degrees of freedom; DFU, diabetic foot ulcer; M, mean; OW, open wound; PI, pressure injury; PPECM, porcine placental extracellular matrix; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean; VLU venous leg ulcer

TABLE 8 Results of the Cohen d effect size

| Standardizer | Point estimate | 95% confidence interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| All | 10.95 | 0.65 | 0.40 | 0.91 | |

| DFU | 2.55 | 1.28 | 0.64 | 1.89 | |

| VLU | 10.83 | 1.53 | -0.03 | 3.01 | |

| PI | 7.64 | 0.89 | 0.20 | 1.55 | |

| OW | 13.49 | 0.60 | 0.25 | 0.95 | |

Abbreviations: DFU, diabetic foot ulcer; OW, open wound; PI, pressure injury; VLU venous leg ulcer.

A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the number of PPECM applications and wound surface area at each successive application, shown in Table 9. To account for varying treatment durations, healed wounds were assigned an area of 0 cm2 for all subsequent time points for the analysis. Across the cohort, a weak positive correlation was observed between the cumulative number of applications per wound and the corresponding wound area; however, none of the associations were statistically significant (all p>0.05). A similar non-significant, weakly positive pattern was evident across all individual subgroups.

TABLE 9 Results of the Pearson correlation coefficient to determine correlations between the number of PPECM applications and wound area after each PPECM application

| App 1 | App 2 | App 3 | App 4 | App 5 | App 6 | App 7 | App 8 | App 9 | App 10 | App 11 | App 12 | App 13 | App 14 | App 15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Pearson correlation | 0.238 | 0.286 | 0.316 | 0.332 | 0.322 | 0.297 | 0.290 | 0.312 | 0.301 | 0.284 | 0.275 | 0.245 | 0.241 | 0.213 | 0.212 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.044 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.019 | 0.038 | 0.042 | 0.072 | 0.074 | |

| N | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | |

| DFU | Pearson correlation | 0.166 | 0.192 | 0.236 | 0.309 | 0.349 | 0.294 | 0.301 | 0.352 | 0.298 | 0.287 | 0.282 | 0.242 | 0.214 | 0.211 | 0.194 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.510 | 0.444 | 0.346 | 0.212 | 0.156 | 0.236 | 0.224 | 0.151 | 0.230 | 0.247 | 0.257 | 0.334 | 0.395 | 0.401 | 0.441 | |

| N | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | |

| VLU | Pearson correlation | 0.917 | 0.850 | 0.926 | 0.914 | 0.924 | 0.914 | 0.954 | 0.963 | 0.976 | 0.966 | 0.931 | 0.976 | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0.946 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.083 | 0.150 | 0.074 | 0.086 | 0.076 | 0.086 | 0.046 | 0.037 | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.069 | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.054 | |

| N | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| PI | Pearson correlation | 0.156 | 0.203 | 0.209 | 0.187 | 0.196 | 0.137 | 0.156 | 0.190 | 0.192 | 0.187 | 0.167 | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.187 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.629 | 0.528 | 0.515 | 0.562 | 0.542 | 0.670 | 0.628 | 0.554 | 0.550 | 0.561 | 0.605 | 0.608 | 0.608 | 0.608 | 0.561 | |

| N | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | |

| OW | Pearson correlation | 0.317 | 0.369 | 0.399 | 0.426 | 0.400 | 0.396 | 0.384 | 0.404 | 0.408 | 0.383 | 0.348 | 0.322 | 0.309 | 0.253 | 0.258 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.032 | 0.048 | 0.059 | 0.126 | 0.118 | |

| N | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

Abbreviations: App, application; DFU, diabetic foot ulcer; OW, open wound; PI, pressure injury; PPECM, porcine placental extracellular matrix; VLU venous leg ulcer

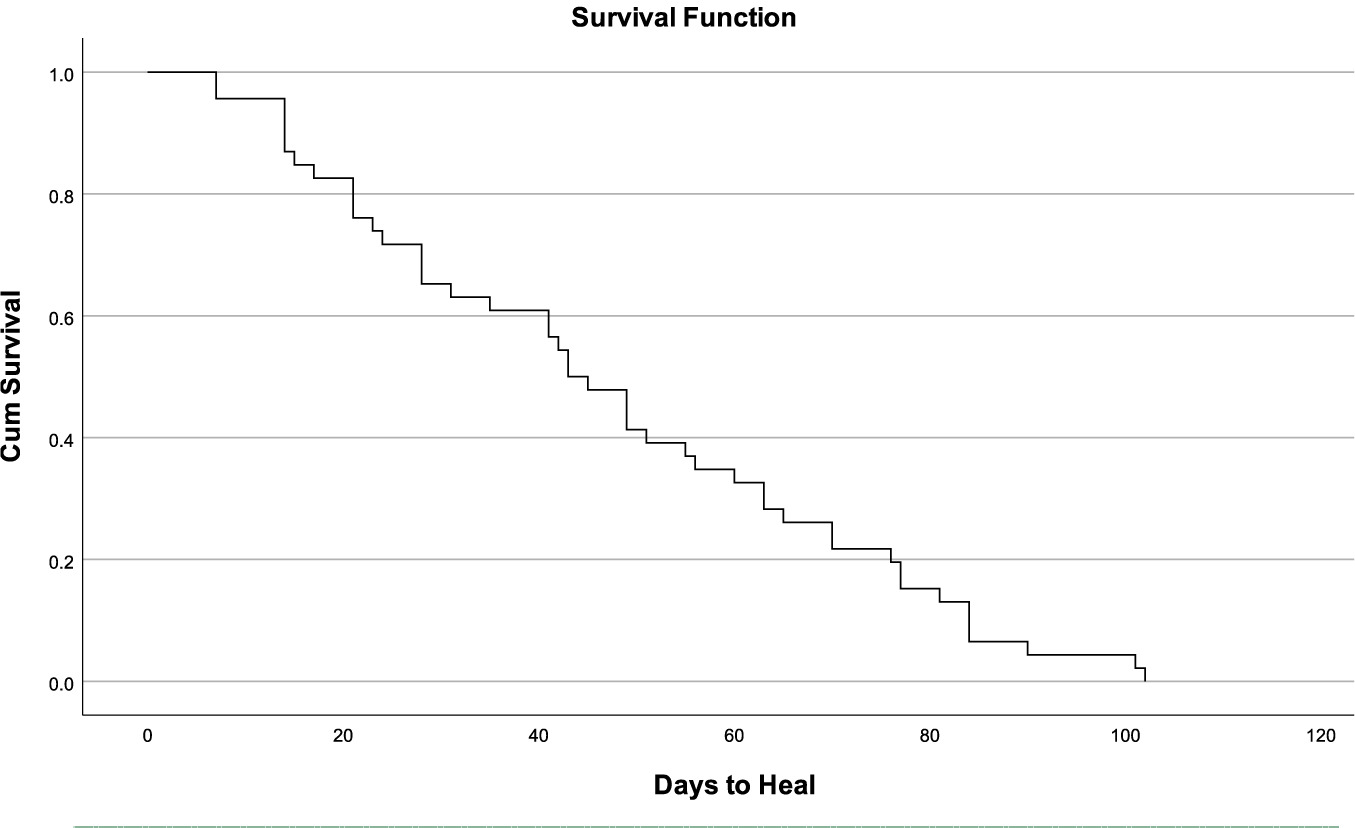

A Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to predict time to complete epithelialization in the 46 wounds that achieved complete closure. The event of interest was defined as complete wound healing, with a time-to-event measured in days from the first PPECM application (range: 7–102 days). The analysis yielded a median healing time of 43 days (95% CI: 36–56 days). The resulting survival curve demonstrated a steady decline in the proportion of unhealed wounds over time, approaching zero by approximately 100 days. This trajectory indicates that the probability of wounds remaining unhealed diminished progressively, with the majority of healable wounds in this cohort achieving complete closure within 14 weeks of initiating PPECM therapy. The Kaplan Meier survival curve to determine the probability of days to healed wounds is shown in Table 10, and the survival curve line graph is shown in Figure 2.

TABLE 10 Results of the Kaplan Meier Survival Curve to determine the probability of days to healed wounds

| Meana | Median | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% confidence interval | 95% confidence interval | ||||||

| Estimate | Std error | Lower bound | Upper bound | Estimate | Std error | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| 47.239 | 3.941 | 39.514 | 54.964 | 43.000 | 3.876 | 35.404 | 50.596 |

aEstimation is limited to the largest survival time if censored.

FIGURE 2 Results of the Kaplan Meier Survival Curve to determine the probability of days to healed wounds as line graph.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis evaluated the clinical outcomes of chronic wounds treated with Innovamatrix™, with particular emphasis on closure rates and PAR across multiple PPECM treatment applications. A statistically and clinically significant reduction in mean wound surface area was observed following the treatment series, with large effect sizes demonstrated across diverse chronic wound etiologies. Additional measures included the average number of applications needed for complete healing and the PAR recorded after each application. Moreover, survival analysis using Kaplan-Meier curves highlighted variations in healing duration, suggesting improved prediction of recovery trajectories with continued PPECM application. While some wounds achieved closure after a single application, it is possible that these were approaching healing under SOC alone; however, all met criteria for refractory wounds prior to PPECM initiation.

Although the management of chronic wounds remains guided by etiology-specific principles, evidence-based standards of care universally emphasize the establishment and maintenance of a clean, uninfected wound bed, typically achieved through aggressive debridement. SOC modalities remain the cornerstone of wound therapy. Nevertheless, the present retrospective analysis provides further evidence supporting the adjunctive use of PPECM alongside conventional treatment protocols, demonstrating an improved probability of complete re-epithelialization and greater PAR in recalcitrant chronic wounds.

This retrospective review affirms the effectiveness of PPECM across a broad spectrum of chronic wound etiologies, such as chronic DFUs, VLUs, pressure injuries, and open wounds that failed to heal or adequately reduce in size with conventional SOC methods. Interpretation of VLU outcomes is limited by the small sample size. The closure rates were consistent with those previously reported for CAMP in DFUs and VLUs,7 suggesting the therapeutic mechanism of PPECM targets shared pathophysiological pathways that perpetuate impaired healing in chronic wounds, irrespective of underlying etiology. In this cohort, full wound resolution was generally accomplished after six applications, highlighting the consistency and reliability of this modality in real-world clinical settings. These findings align closely with the extensive retrospective Medicare analysis by Carpenter et al, which similarly demonstrated high rates of complete healing across diverse chronic wound types using CAMPs in routine private practice, further confirming the generalizability of advanced CAMP modalities in heterogeneous real-world settings.7

Rigorous eligibility standards were applied to strengthen internal validity and to isolate the specific contribution of PPECM in treating chronic wounds. Patients with severe systemic inflammatory conditions (e.g., advanced pyoderma gangrenosum) or those undergoing active oncologic therapy were excluded, as such comorbidities could confound the attribution of healing effects directly to PPECM. These stringent criteria minimized extraneous variables, thereby enhancing the study’s reliability and the validity of conclusions regarding the impact of PPECM. Although these exclusions suggest limited applicability in highly complex patients, existing research shows favorable results, including accelerated closure, with repeated CAMP applications in similar challenging populations.8-10 Thus, the exclusions applied herein are not absolute contraindications to CAMPs in complex cases; instead, they serve to create a controlled, applicable dataset to guide SOC decisions for the broader chronic wound community.

Furthermore, the present investigation offers a distinctive contribution by examining the application of PPECM within outpatient community-based settings, a context that remains markedly underrepresented in current research on advanced wound therapies. A principal advantage of this care-delivery model is the reduction of patient travel demands and expenses that frequently impede consistent engagement with tertiary or hospital-affiliated wound centers. While community, or home-based care, may limit the thoroughness of serial debridement and preparation— reducing efficacy relative to advanced facilities—it substantially enhances equitable access to biologic treatments. By alleviating logistical obstacles, community deployment of PPECM extends evidence-based care to historically underserved populations, expanding the demographic and socioeconomic reach of beneficiaries and promoting inclusivity in chronic wound management.

Increasing amounts of high-quality data support the value of CAMPs in producing significant dimensional reductions in chronic wounds.11 This study contributes distinctively by providing granular, longitudinal documentation of wound surface area trajectory following each PPECM application throughout a 15-week treatment interval, covering various wound etiologies. Ongoing assessments revealed consistent mean reductions in area per application. Importantly, the treatment response for pressure ulcers and chronic open wounds matched and slightly exceeded that for the more extensively studied DFUs and VLUs. Average PAR per application, and the rate of achieving full wound closure, aligned with or exceeded benchmark outcomes reported in prior randomized controlled trials and large-scale wound registries for DFUs and VLUs.12 Taken together, these findings demonstrate reproducible, benchmark-equivalent or superior healing trajectories across diverse chronic wound etiologies with serial PPECM application. Accordingly, the use of PPECM in the management of chronic wounds is no longer investigational, but rather an evidence-based advanced treatment modality supported by robust clinical outcomes in wound medicine practice.

The findings of this study challenge the prevailing regulatory and reimbursement paradigms that disproportionately prioritize DFUs and VLUs as the primary indications for application of advanced CAMPs, and frequently marginalizing pressure injuries and other non-healing chronic wounds. While ideal CAMP dosing has been well-established for DFUs and VLUs through pivotal trials, corresponding data for other chronic wound etiologies are limited. The present analysis provides robust preliminary evidence of a consistent dose-dependent relationship across all etiologic categories, suggesting that etiology-specific restrictions on CAMP use or reimbursement may not be warranted or realistic when objectively evaluated on therapeutic efficacy.

Limitations

As with all retrospective investigations, the present study is subject to several inherent limitations that warrant consideration when interpreting its findings. First, the modest sample size constrained statistical power and the precision of effect-size estimates, particularly within etiology-specific subgroups. This limitation likely contributed to the absence of a significant Pearson correlation, attributable in part to progressive attrition of data points as wounds achieved closure, and affected the extensive statistical analyses performed on small subgroups. A larger cohort would strengthen the robustness of the observations and facilitate more nuanced exploration of factors influencing treatment response. Additionally, wounds healing after minimal applications raise questions about the incremental benefit of PPECM versus continued SOC.

Data were primarily extracted from EHRs, with manual chart review used for validation. Although this hybrid approach mitigated some deficiencies associated with fully automated extraction, it remains dependent on the accuracy of clinical documentation and diagnostic coding. Inaccuracies in coding could introduce misclassification bias, potentially affecting both participant selection and the attribution of outcomes.

Representation of hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) was limited, precluding a comprehensive comparison across care-delivery settings. Although the cohort encompassed private clinics, mobile wound-care services, and long-term care facilities, the underrepresentation of HOPDs raises the possibility of selection bias, given potential differences in patient demographics, wound severity, clinician expertise, and adherence to evidence-based protocols between community-based and hospital-based environments. Consequently, the study population was predominantly aged >65 years, which may restrict the extrapolation to younger patients. Future investigations should adopt multicenter designs that incorporate HOPDs, diverse payer models, and broader age distributions to yield more representative evidence capable of informing both clinical practice and health policy.

Outcomes were not stratified by wound depth or the presence of exposed critical structures (e.g. bone, tendon, etc.). Deep wounds complicated by osteomyelitis, tendinopathy, or contaminated implants present distinct pathophysiological challenges that may limit the efficacy of primarily dermal-oriented regenerative matrices, such as PPECM. Dedicated studies examining its performance in stage IV pressure injuries, tendon-exposed DFUs, and complex surgical dehiscence with structural involvement are required to delineate therapeutic boundaries and guide appropriate escalation to alternative advanced modalities.

A fundamental limitation is the absence of a concurrent control cohort managed exclusively with SOC interventions without PPECM. Without such a comparator, observed reductions in wound area cannot be fully disentangled from the natural, although typically extended, healing trajectory achievable with optimized SOC alone. Contemporary real-world data on the spontaneous healing rates of untreated or SOC-managed chronic wounds across all etiologies remain scarce, underscoring the need for large-scale prospective registries that document natural history in the absence of biologic augmentation.

Although the primary objective of this analysis was to characterize per-application efficacy rather than to establish superiority, the inclusion of matched SOC-only controls or propensity-score-matched analyses from existing registries would substantially strengthen causal inference in subsequent investigations. Pragmatic clinical trials or registry-based comparative effectiveness studies could provide ecologically valid benchmarks while preserving real-world applicability.

Finally, comprehensive health-economic evaluations that incorporate direct and indirect costs are essential for quantifying the incremental value of PPECM across wound etiologies. The comparable efficacy observed in pressure injuries and non-healing surgical wounds relative to DFUs and VLUs, supports the potential development of etiology-agnostic treatment protocols that could streamline care delivery and reduce practice variation. However, reimbursement decisions are frequently governed by cost-effectiveness thresholds; thus, etiology-specific pharmacoeconomic modeling is particularly needed for indications with historically limited evidence. Addressing these gaps, alongside longer-term endpoints, such as recurrence rates and health-related quality of life, will be instrumental in overcoming existing barriers and facilitating equitable integration of PPECM into evidence-based chronic wound management paradigms.

Conclusion

Chronic wounds represent a significant global public health challenge, contributing substantially to morbidity, diminished quality of life, excess mortality, and considerable economic burden on healthcare systems. The present retrospective analysis demonstrates that Innovamatrix™ yields high rates of complete wound closure and PAR in pressure injuries and non-healing open wounds—outcomes that are comparable to, and in specific parameters superior to, those observed in the more extensively investigated DFUs and VLUs. The preliminary findings challenge current etiology-specific restrictions embedded in regulatory approvals and reimbursement policies and provide preliminary empirical support for clinical practice guidelines that expand coverage to historically underrepresented chronic wound categories.

Far from functioning as a standalone intervention, PPECM emerges as a versatile, potentially etiology-agnostic advanced therapy that delivers consistent efficacy across diverse wound types when integrated with optimized SOC protocols. To fully realize this potential, future research should prioritize the identification and validation of patient -and wound-level predictors of therapeutic response, thereby enabling more precise, personalized application. Rigorous, multicenter prospective trials focused on pressure injuries and chronic open wounds are essential to corroborate the present observations, establish optimal treatment algorithms, and generate the high-quality evidence required to broaden clinical adoption and secure equitable reimbursement across the full spectrum of chronic wound etiologies.